Discharge to skilled-care or rehabilitation following elective anterior cervical discectomy and fusion increases the risk of 30-day re-admissions and post-discharge complications

Introduction

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is one of the most common procedures done for management of degenerative pathology of the cervical spine. With excellent outcomes and low complication rates (1), it is widely regarded as the gold-standard treatment for cervical spondylosis. Literature has reported an 800% increase in the total number of ACDF cases from 1990–2004 which are expected to rise even further (2,3). With a shift toward value-based and bundled payment models of healthcare, there has been increasing interest in identifying areas of cost reduction.

Post-acute care (PAC) has been found to be a significant driver of cost-variation in bundled reimbursements for spinal fusions made to hospitals, with reports showing up to 39% variation in payments (4). It appears that multiple factors such as surgeon/patient preference as well as a lack of PAC guidelines lead to variation in utilization. Past arthroplasty literature has concluded that the use of such post-acute care facilities are not associated with improved outcomes (5,6). With regard to spine surgeries, current evidence is scant and limited. Cook et al explored the impact of post-discharge care and outcomes following lumbar spine surgery, and have concluded the negative impact of post-acute rehabilitation services such as inpatient rehabilitation units, skilled care facilities, long term-hospitals and home-health services on 30-day re-admissions (7). Given the limitations of administrative database research, such as the inability to control for confounding factors such as prior functional status, as well as a gap in the knowledge with regards to the impact of discharge destination on post-discharge outcomes in cervical fusion, there is need for further research aimed at understanding outcomes of patients discharged to these facilities so that appropriate pre-operative planning can be done to minimize poor outcomes and consequently excess healthcare costs.

We sought to collate evidence using a large national multi-center surgical database to assess the clinical impact of continued post-discharged inpatient care (skilled care facility or inpatient rehabilitation unit) on 30-day complications, readmissions and mortality after elective ACDF.

Methods

Database

This was a retrospective study done using the 2015–2016 American College of Surgeons (ACS)—National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database. The ACS-NSQIP database collects surgical information from more than 500 hospitals across the United States. Data is recorded for more than 150 preoperative, intra-operative and post-operative variables up to 30 days following the operation. The data are collated by trained surgical and clinical reviewers with audit reports showing an inter-reviewer disagreement rate of below 2% (8).

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for ACDF (CPT-22551, 22552) were used to identify patients from the database. Only elective ACDFs being done for ≤3 levels were included in the study. Patients undergoing additional posterior cervical spine procedures (instrumentation, laminectomy, laminotomy, etc.) were excluded from the analysis. In addition, patients undergoing surgery for cervical fracture, malignancy and spinal deformity were also excluded. Finally data were filtered to remove missing variables and prevent any confounding in analysis. A total of 15,624 patients were finally included for descriptive and statistical analysis.

Definition of variables studied

For baseline clinical characteristics and demographics of the study population, the following variables were collected—age (dichotomized into <65 and ≥65 years of age), gender, race (White, African-American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific and Unknown/Not reported), body mass index (BMI), co-morbidities, type of anesthesia used (general vs. other), location of surgery (inpatient vs. outpatient), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, transfer status (Home, acute care hospital/inpatient, outside emergency department, nursing home and other), quarter of admission (January-March, April-June, July-September and October-December), number of levels fused (single- vs. 2- vs. 3-level), total operative time (0–90, 91–150 and >150 min) and length of stay (<3 vs. ≥3 days).

Discharge disposition was defined as discharge to skilled-care or rehabilitation vs. home. Those patients being discharged to other destinations such as acute-care hospitals, unskilled facilities and assisted living facilities were excluded from the analysis to ensure that the results are relevant to the objective of the study.

Thirty-day complications that were studied included wound complications [superficial surgical site infection (SSI), deep SSI and organ space SSI], cardiac complications (myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest), respiratory complications (pneumonia, unplanned intubations and post-operative ventilator requirement >48 hours), thromboembolic complications [deep venous thrombosis (DVT)] and pulmonary embolism (PE) sepsis related complications (sepsis or septic shock), renal complications (acute renal failure and progressive renal insufficiency), urinary tract infection (UTI), and stroke. Another variable defined as “any complication” was created that recorded the presence of at least one of the above mentioned complications in 30-day post-surgery period. All complications were separately identified during index hospital stay (pre-discharge) and after discharge to nursing care/rehabilitation (post-discharge) to allow for adjusted analysis. Thirty-day readmissions, unplanned re-operations and mortality were also analyzed as part of our study.

Statistical analysis

Baseline clinical characteristics were described using descriptive statistics.

To identify significant predictors, Pearson-Chi square test was used to conduct crude analysis to assess for variables significantly associated with discharge to skilled care/rehabilitation. All significant factors with a P value of less than 0.1 were then entered into a multivariate logistic regression model. All variables with a P value of less than 0.05 following adjustment were considered significant predictors for a discharge to skilled-care/rehabilitation.

To assess the clinical impact of discharge to skilled-care or rehabilitation facility on post-operative outcomes, unadjusted analysis to assess significant associations from discharge to skilled-care/rehabilitation were conducted using Pearson-Chi Square analysis. For each variable with a P value of less than 0.1, a separate multivariate backward elimination logistic model was set up to assess the impact of discharge destination on post-operative outcome while adjusting for all baseline clinical characteristics.

Results

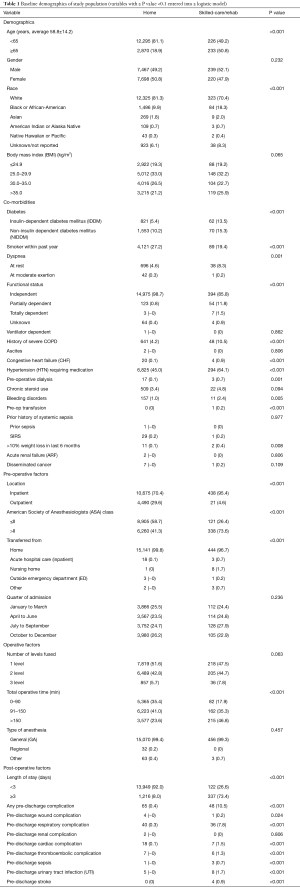

A total of 15,624 patients were included in the study after applying the appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria. Baseline clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. A majority of the patients were below the age of 65 years (N=12,521; 80.1%). The study population was equally divided between male (N=7,706; 49.3%) and female (N=7,918; 50.7%) patients. A majority of the procedures were single-level (N=8,037; 51.4%) followed by 2-level (N=6,694; 42.8%) and 3-level (N=893; 5.7%). Around 90% (N=14,071) of patients had a LOS <3 days. A total of 459 patients (2.9%) were discharged to a skilled-care or rehabilitation facility.

Full table

Predictors of discharge to skilled-care or rehabilitation facility

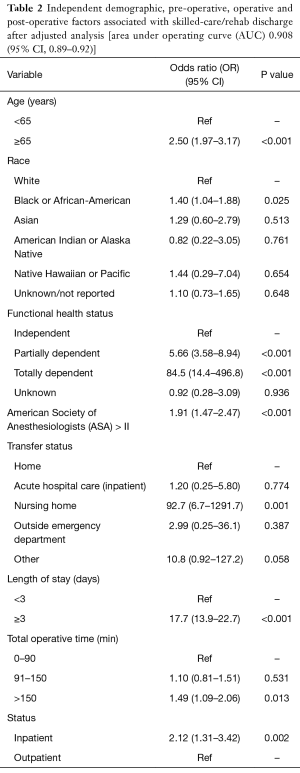

Unadjusted analysis for significant predictors is shown in Table 1. Following adjusted analysis, an age of ≥65 years (OR =2.50; 95% CI: 1.97–3.17; P<0.001), Black or African-American race (OR =1.40; 95% CI: 1.04–1.88; P=0.025), partially dependent (OR =5.66; 95% CI: 3.58–8.94; P<0.001) or totally dependent (OR =84.5; 95% CI: 14.4–496.8; P<0.001), a LOS ≥3 days (OR 17.7; 95% CI: 13.9–22.7; P<0.001), a total operative time >150 min (OR =1.49; 95% CI: 1.09–2.06; P=0.013), ASA grade > II (OR =1.91; 95% CI: 1.47–2.47; P<0.001) and inpatient surgery (OR =2.12; 95% CI: 1.31–3.42; P=0.002) were significant predictors associated with a discharge to skilled care or rehabilitation facility (Table 2). The area under curve (AUC) of the regression model was 0.908 (95% CI: 0.89–0.92) indicating a high predictive probability.

Full table

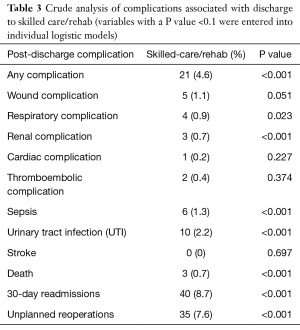

Clinical impact of discharge to skilled-care or rehabilitation facility

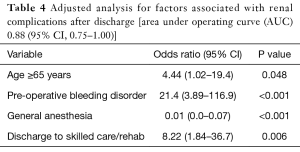

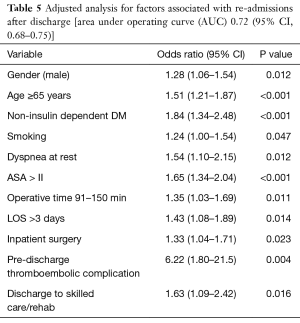

Unadjusted analysis for significant associations between discharge to skilled care or rehabilitation and occurrence of post-operative complications is shown in Table 3. Following adjustment for pre-operative, operative and post-operative factors from Table 1, using separate backward elimination logistic regression models for each variable, discharge to skilled care or rehabilitation was an independent significant risk factor for renal complications (OR =8.22; 95% CI: 1.84–36.7; P=0.006) (Table 4) and 30-day readmissions (OR =1.63; 95% CI: 1.09–2.42; P=0.016) (Table 5). Both models had good predictive probability with an AUC of 0.88 and 0.72 for renal complications and 30-day re-admissions, respectively.

Full table

Full table

Full table

Discussion

The current study’s results show that a discharge to a skilled-care or rehabilitation facility is associated with higher odds of developing post-discharge renal complications and 30-day readmissions. This study also identifies significant predictors associated with discharge to a skilled-care or rehabilitation facility following ACDF. We found that older, sicker and minority patients with a prolonged duration of surgery were more likely to be discharged to skilled-care or rehabilitation facility.

With bundled payments becoming a major key player in elective spine surgeries in the near future (9), it is necessary to identify clinical outcomes in health-care areas, such as post-acute care, which have been shown to be major drivers for cost-variations in episode payments (4). Despite studies reporting a steady increase in discharge to skilled nursing facilities (SNF) for post-acute care, little is known about their outcomes (10). Furthermore, a 2006-based study reported that around 24% of Medicare beneficiaries are re-admitted back to the hospital following discharge to a skilled-nursing facility, with a total cost burden for these unplanned re-hospitalizations amounting to $4 billion USD (11). Though arthroplasty literature has shown no functional benefit in the use of post-acute care facilities vs. home-based care, recent spine surgery pertinent investigations have shown that inpatient rehabilitation programs may improve functional dependence measures and discharge rate to the home/community (12).

We found 8.6% of patients who were discharged to a skilled-care facility or rehabilitation were re-admitted to the hospital within 30 days, with a significant association present between discharge to skilled-care/rehab facility and re-admission rate. The current study’s findings following post-acute care is similar to that reported for lumbar fusion surgeries by Cook et al. (7). Though studies on post-discharge outcomes are limited in spine literature, other surgical literature has reported similar findings of SNF discharge negatively impacting re-admissions (10,11,13). However, it is imperative to keep in mind the variation in the nature of surgical procedures within the studies. Fernandes-Taylor et al. assessed 30-day readmissions and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries discharged to SNF following an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair or lower extremity re-vascularization (13). Similarly, Ottenbacher et al. reported that around 12% of patients who were discharged to a rehabilitation facility following acute hospitalization for stroke, lower extremity fracture, joint replacement, debility, neurologic disorders and brain dysfunction were re-admitted, with 50% of those cases occurring within 11 days following discharge (14). Regardless, given that 30-day readmissions are now commonly tied with regard to hospital metrics the findings of the study are particularly important from a health-care economic point-of-view (15).

A possible reason for the current study’s finding could be due to variation in the quality of care being provided for in skilled-care facilities across the country (16). Moreover, recent studies have mentioned that often patients are not given quality-of-care data about SNF when discharged from hospitals (17). Therefore, the quality of care being provided in these facilities may have a bearing on the length of stay, complications and return to function/community. Future interventions for improving quality and metrics of nursing care facilities with implementation of uniform infection prevention protocols may be beneficial.

Another plausible explanation to these findings can be partly explained by the continued exposure to health-care workers, due to a high “monitoring” effect seen in inpatient care facilities. As Strosberg suggested (18), one way of combating this “monitoring” effect is to prioritize a discharge to home without the need of skilled-health monitoring. Regardless, the findings stress the need for pre-operative medical and discharge optimization in high-risk patients to ensure discharge destination is appropriately met according to their needs without increasing the risk of re-admissions.

Though previous studies have explored predictors of discharge destination following elective ACDFs they have primarily compared outcomes between home vs. non-home discharge (19). Considering the different types of facilities in the non-home group as well as the differences in the quality of care and types of patients being catered to in each, the current study effectively focuses on discharges to skilled-care and rehabilitation only. We noticed that older patients (age ≥65 years) and Black/African-American patients were 2.5 and 1.4 times more likely to be discharged to a skilled-care or rehabilitation facility following surgery. This finding is similar to past orthopaedics and general surgery literature (10,20-22).

A partially dependent or totally dependent functional health status was associated with a higher risk of discharge to skilled-care. This is to be expected given that these patients have difficulty mobilizing and would require rehabilitation facility use following surgery (23). In addition, these patients may also require continuing medical care as compared to normal active patients (24,25). However, Di Capua et al. in their study state that poor functional health status may be linked to myelopathy and can be a common presenting feature in patients undergoing ACDF (19). Myelopathy is known to significantly affect activities of daily living (26). More importantly, myelopathy in chronic cases can also impact functioning of vital organ systems as well. Toyoda et al. showed that expiratory flow may be impaired or incomplete in patients with chronic cervical myelopathy (27). This is particularly important as these patients are more likely to require intensive care following surgery.

The prolonged operative time as a significant predictor for skilled-care or rehabilitation following surgery could be partly explained by the complexity and/or severity of the case. However, NSQIP does not contain granular data with regard to clinical and radiological severity of the diseases to allow comparison of severity of disease.

There are some limitations to our analysis. First, ACS-NSQIP records data only up to 30 days after surgical procedure, precluding analysis of longer-term outcomes. Second, it does not record data specific to extended care facilities, such as the time spent in in-patient care facilities and subsequent rates of successful discharge to community. We did not have information about socioeconomic and insurance statuses of patients as these have been known impact discharge disposition. Finally, majority of the hospitals in NSQIP are academic medical centers and therefore, the findings may not be uniformly generalized on a national level.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our findings are the first to show that discharge to skilled-care/rehabilitation facility are negatively associated with 30-day readmissions and complications. Early identification and optimization of such patients may not only be helpful in reducing hospital length of stay, but also allow care-givers to pre-operatively risk stratify patients to ensure utilization of post-discharge skilled-care and rehabilitation facilities in patients, when absolutely required, to positively influence the quality, and eventually the cost of care after elective ACDF.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study did not require ethical approval from our local Institutional Review Board.

References

- Fountas KN, Kapsalaki EZ, Nikolakakos LG, et al. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion associated complications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2310-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marawar S, Girardi FP, Sama AA, et al. National trends in anterior cervical fusion procedures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:1454-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patil PG, Turner DA, Pietrobon R. National trends in surgical procedures for degenerative cervical spine disease: 1990-2000. Neurosurgery 2005;57:753-8; discussion -8.

- Schoenfeld AJ, Harris MB, Liu H, et al. Variations in Medicare payments for episodes of spine surgery. Spine J 2014;14:2793-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kathrins B, Kathrins R, Marsico R, et al. Comparison of day rehabilitation to skilled nursing facility for the rehabilitation for total knee arthroplasty. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2013;92:61-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mahomed NN, Davis AM, Hawker G, et al. Inpatient compared with home-based rehabilitation following primary unilateral total hip or knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:1673-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cook C, Coronado RA, Bettger JP, et al. The association of discharge destination with 30-day rehospitalization rates among older adults receiving lumbar spinal fusion surgery. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2018;34:77-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- User Guide for the 2016 ACS NSQIP Participant Use File (PUF).

- Culler SD, Jevsevar DS, Shea KG, et al. Incremental Hospital Cost and Length-of-Stay Associated With Treating Adverse Events Among Medicare Beneficiaries Undergoing Lumbar Spinal Fusion During Fiscal Year 2013. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:1613-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hakkarainen TW, Arbabi S, Willis MM, et al. Outcomes of Patients Discharged to Skilled Nursing Facilities After Acute Care Hospitalizations. Ann Surg 2016;263:280-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, et al. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:57-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perez-Bravo EJ, Verma N, Suriyakhamhaengwongse A, et al. Poster 479: Effectiveness of Inpatient Rehabilitation in Improving Functional Outcomes After Spinal Fusion Surgery. PM&R 2017;9:S285. [Crossref]

- Fernandes-Taylor S, Berg S, Gunter R, et al. Thirty-day readmission and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries discharged to skilled nursing facilities after vascular surgery. J Surg Res 2018;221:196-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ottenbacher KJ, Karmarkar A, Graham JE, et al. Thirty-day hospital readmission following discharge from postacute rehabilitation in fee-for-service Medicare patients. JAMA 2014;311:604-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hwang YJ, Minnillo BJ, Kim SP, et al. Assessment of healthcare quality metrics: Length-of-stay, 30-day readmission, and 30-day mortality for radical nephrectomy with inferior vena cava thrombectomy. Can Urol Assoc J 2015;9:114-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neuman MD, Wirtalla C, Werner RM. Association between skilled nursing facility quality indicators and hospital readmissions. JAMA 2014;312:1542-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tyler DA, Gadbois EA, McHugh JP, et al. Patients Are Not Given Quality-Of-Care Data About Skilled Nursing Facilities When Discharged From Hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:1385-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strosberg DS, Housley BC, Vazquez D, et al. Discharge destination and readmission rates in older trauma patients. J Surg Res 2017;207:27-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Di Capua J, Somani S, Kim JS, et al. Predictors for Patient Discharge Destination After Elective Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017;42:1538-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sacks GD, Lawson EH, Dawes AJ, et al. Which Patients Require More Care after Hospital Discharge? An Analysis of Post-Acute Care Use among Elderly Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2015;220:1113-21.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Pablo P, Losina E, Phillips CB, et al. Determinants of discharge destination following elective total hip replacement. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:1009-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aldebeyan S, Aoude A, Fortin M, et al. Predictors of Discharge Destination After Lumbar Spine Fusion Surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:1535-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suskind AM, Jin C, Cooperberg MR, et al. Preoperative Frailty Is Associated With Discharge to Skilled or Assisted Living Facilities After Urologic Procedures of Varying Complexity. Urology 2016;97:25-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mor V, Wilcox V, Rakowski W, et al. Functional transitions among the elderly: patterns, predictors, and related hospital use. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1274-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Severson MA, Smith GE, Tangalos EG, et al. Patterns and predictors of institutionalization in community-based dementia patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42:181-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ganguly K, Abrams GM. Management of chronic myelopathy symptoms and activities of daily living. Semin Neurol 2012;32:161-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toyoda H, Nakamura H, Konishi S, et al. Does chronic cervical myelopathy affect respiratory function? J Neurosurg Spine 2004;1:175-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]