En bloc resection in the spine: a procedure of surgical oncology

It is really stating the obvious to say that a surgical procedure aiming to remove a tumor should be planned based on oncological principles.

En bloc resection is a procedure of surgical oncology aiming to remove a tumoral mass in its entirety, completely surrounded by a continuous layer of healthy tissue

The healthy tissue surrounding the tumor has been named “margin”: its quality and its thickness qualifies the procedure from an oncological point of view, affecting the local and systemic prognosis (1,2). This procedure became the golden standard in the treatment of bone tumors of the limbs in the seventies, after the introduction of the protocols of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. The effects of these new drugs on the tumoral mass (volume reduction, harder consistency) allowed to develop techniques of surgical resection the tumor without sacrificing the limb (so called “limb salvage procedures”) (3).

En bloc resection of spine tumors obviously require a deep knowledge of specific regional issues of surgical anatomy, as the margins are possibly represented by anatomical structures of relevant functional role.

Reading the literature on spine tumors, the oncological principles seem to receive less consideration than the details of surgical techniques and the application of up-to-date technologies (4).

En bloc resection in spine tumors requires spine surgery skill and multidisciplinary competences, and is a very interesting argument for discussion and sharing different opinion and experiences: newest techniques should be applied to improve the outcome and to make surgery less difficult, less morbid and more reproducible, but the use of these new tools should always be secondary to the fulfilling of oncological principles. Technologies are the means, not the end.

Some papers are dedicated to functional results (5) undeniably important, but—differently from metastases—secondary to oncological principles in the decision-making process of primary tumors

Focus should be concentrated on the local recurrence rate, which is the best indicator of the validity of a procedure of surgical oncology (2).

Surgical techniques to perform en bloc resection in the spine have been frequently proposed irrespective of tumor extension: the most popular technique of en bloc resection of a spine tumor, described by Roy-Camille et al. (6) and later by Tomita et al. (7) has an oncological validity only if the tumor is not growing over the antero-lateral vertebral body cortex, otherwise the blunt manual dissection will breach the tumor margin.

Tomita proposed the term Total En bloc Spondylectomy, which in my perspective, is not oncologically appropriate. In fact, the target is not to resect en bloc the whole vertebra, but to resect en bloc the tumor with an appropriate margin. This sometimes does not require to remove the whole vertebra.

Bertil Stener was the pioneer of the application to the spine the oncologic principles generally accepted for the gastrointestinal tumors (8). His detailed reports of the surgical planning of en bloc resections are till now extremely useful and exhaustive as a guide to learn how oncological principles can guide the surgical planning. His work represents a watershed between precedent pioneers’ activity and strict adherence to the oncological principles at that time developed. It is here the place to acknowledge the experiences by Janos Szava, professor of Orthopedics at Marosvásárhely (Romania). He performed some spine tumor resections in the 1950s which are still unknown by most of us due to language and political barriers (9).

Several articles were later on written describing different approaches and different combinations of approaches. Some of them are particularly relevant as have a strong oncological commitment, targeting the surgical procedure on the achievement of a full free-tumor margin resection even with the sacrifice of relevant anatomical structures: dura (10), cervical nerve roots (11) cauda equina and spinal cord (12), major vascular structures and visceral organs (13).

Among the details of technique, the technique of osteotomy is the most discussed one. Roy-Camille (6) and Stener (8) years before, proposed to perform the osteotomy by the combined use of a Gigli and osteotomes. In those papers it is stressed on the risk of losing the control of the Gigli saw during the final steps ending in incidental injury of the dural sac. Tomita (7) proposed a thinner saw and an original set of instruments—relying on the hands of the assistant—both to protect the dura from accidental injuries while cutting anterior to posterior, both to perform a coronal section of the pedicles, allowing to finalize the spondylectomy by achieving two specimens.

An original proposal by Gasbarrini et al. is the malleable protector of the dura (14) to be inserted between the dura and the posterior vertebral wall and fixed to one of the rods: it is a solid and sound protection from accidental injuries without relying on the hands of a surgeon

In a recent well documented article by Shah et al. (15) an interesting use of the threadwire saw is proposed. It is an interesting tip, whose application however is limited to some part of the thoracic and lumbar spine: it is not applicable to high thoracic spine neither to low lumbar spine.

According to different personal experiences and manuality, chisels, osteotomes, ultrasound osteotome, high speed burr can be indifferently used to perform the osteotomies without affecting the final outcome, provided the resection is finally achieved with appropriate margin. For the purpose of a sound and balanced reconstruction, a perfectly flat osteotomy surface should be obtained, for a full contact with the cage and/or the graft.

It should also be considered that according to the surgical planning, diskectomy (and all the relative tools) can be preferred to osteotomy. In this case, all disk material and cartilage should be removed from the endplates for a better cage positioning and graft incorporation.

In my opinion, we should follow the great message delivered by Bertil Stener in his unforgotten papers: it does not exist a single surgical technique able to perform en bloc resection of all bone tumors in the spine, but the surgical technique should be planned according to the tumor extension, the spine location, the histology, the margins to be achieved (8).

The new frontier is to consider the possibilities offered by new technologies of radiation therapy (RT) and new protocols of chemotherapy to recover margin transgression incidentally occurring or intentionally decided to save anatomical structures according to the patient preferences.

Oncological basis for treatment

The Enneking staging system (1) is a valid and reproducible tool for understanding and staging the biological behavior of bone and soft tissue tumors and for deciding the appropriate surgical procedure from an oncological point of view. This system is based on histological diagnosis and on clinical, laboratory and imaging studies. It also proposed a common terminology to the multidisciplinary team who take care of these diseases.

For simplicity purpose the surgical procedures following the dictates of the Enneking staging system are defined as Enneking appropriate (2)

En bloc resection is recommended in cases of benign aggressive (Enneking stage 3) tumors (i.e., osteoblastomas and giant cell tumors) and low-grade malignant tumors (Enneking stage I A and B) like chordomas and chondrosarcomas. In high grade malignancies (Enneking stage II) like osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma chemotherapy and radiotherapy have a very relevant and essential role.

Once the resection performed, the pathologist must carefully evaluate the tumor margins, as defined by “wide” (a relevant barrier like a fascia or at least healthy bone 1 cm thick) “marginal” (a thin barrier like periosteum) or “intralesional”.

“Intralesional” resection is defined when the surgeon incidentally or intentionally violates the tumor. Violation of the margins significantly worsen the prognosis (2). Intentional intralesional resection [so called intentional transgression to oncological principles (2)] may be an option when the patient does not accept the sacrifice of a functionally relevant element that is closely contiguous to the tumor or has been infiltrated.

The patient however must be fully informed of the higher risk of recurrence after Enneking-inappropriate procedure (2) and that the rate of complications and further tumor recurrence are significantly higher after revision surgery (16).

If patient strongly requires the preservation of anatomical structure to save the function, and notwithstanding the exposition to higher recurrence rate, adjuvant therapy is indicated.

En bloc resection has a limited role in the treatment of spine metastases. The primary goal in these patients is to preserve or improve function and quality of life without unnecessary morbidity. Giving the priority to function, no major anatomical sacrifice with consequent relevant loss of function should be planned. However, in some selected cases, after a multidisciplinary discussion en bloc resection could be proposed to reduce or delete any risk of local recurrence. In the authors’ experience, the indication to en bloc resection is appropriate in single localizations, with full tumor control at the primary site and no involvement of visceral organs, best after long term disease free evolution. The key point in this decision is the lack of sensitivity to medical oncology or radiation oncology treatments: alternatively, less aggressive surgery could be combined with these treatments, reducing the surgical morbidity without reducing the possibility to local cure.

Surgical planning

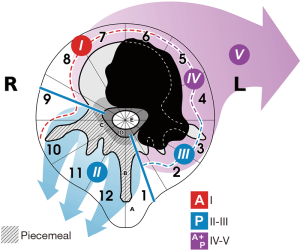

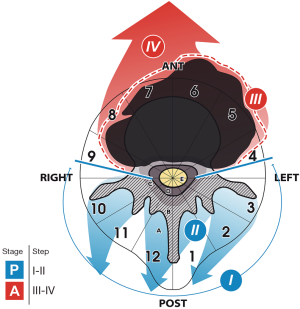

The Weinstein-Boriani-Biagini (WBB) surgical system was proposed in 1997 (17) to stage the extension of spine tumors. It has been adopted in several spine oncology centers and is used in most of spine tumors related articles. The WBB system has been submitted by an international multidisciplinary group of spine tumor experts (18) to a reliability and validity study resulting in a moderate interobserver reliability and substantial intraobserver reliability.

The WBB staging system (17) can be helpful in surgical planning of en bloc resection.

Accordingly, seven types of procedures are here proposed, defined by the approach or the combination of approaches, with several subgroups, ending in a total of ten different surgical strategies.

Single anterior approach (type 1); single posterior approach (type 2) including three subtypes (a, b, c); anterior and then posterior approach (type 3) with three subtypes (a, b, c); first posterior approach, followed by both side anterior approaches (type 4); first posterior approach and then simultaneous anterior and reopening of posterior approach (type 5); anterior, posterior, and then simultaneous anterior (contralateral) and reopening of posterior approach (type 6, mostly performed for L5); posterior approach first and anterior approach as second step (type 7).

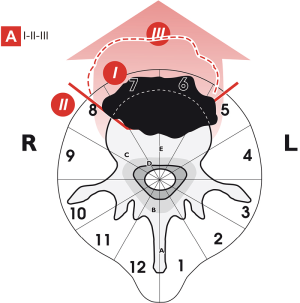

Type 1: Single anterior approach (Figure 1) allows to perform en bloc resection only of small volume tumors arising in the vertebral body of the thoracic and lumbar spine.

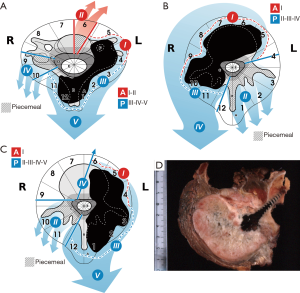

Type 2: Single posterior approach allows to perform many different en bloc resections either on tumors occurring in the posterior elements, either in the vertebral body either eccentrically located (Figure 2).

Type 3: Anterior approach first, posterior second is the strategy proposed to perform en bloc resection of cervical spine tumors (Figure 3A) which involve part of the vertebral body (no sector 6 and 7, otherwise type 4 is suggested) and part of the posterior arch (at least 3 sectors should not be not involved) or in tumors located in the thoracic and in the lumbar spine when the tumor is growing anteriorly in layer A (Figure 3B), or in case of tumor eccentrically growing in the thoracic and lumbar spine (Figure 3C,D) when sagittal osteotomy is considered safe for appropriate margin, without need to remove the whole vertebral body.

Type 4: In some huge tumors of the cervical spine, extending over the midline, three approaches are required for a safe and oncologically appropriate surgery: first step is a posterior approach, the second step is an anterior approach contralateral to the tumor, the third step is an anterior approach on the tumor side (Figure 4)

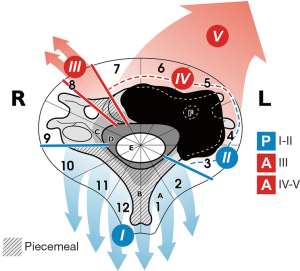

Type 5: This includes two stages: first a posterior approach, then a combined anterior and posterior approach with the patient positioned on side (Figure 5). This demanding technique (associated with the highest rate of morbidity and complications) can be the most appropriate for lumbar tumors expanding anteriorly. This technique was described by Roy Camille for lumbar tumors (6) and is associated with the highest rate of morbidity and complications (16) As an advantage compared to type 3b (Figure 3B), no nerve root is sacrificed if not involved by the tumor.

Type 6: To perform an en bloc resection of a L5 tumor three approaches are suggested: the first stage by anterior approach on the side contralateral to the tumor; a second stage posterior, the third a contemporary anterior and posterior approach with the patient positioned on a side (Figure 6). The safe release the aorta/cava bifurcation is allowed by the bilateral anterior approach.

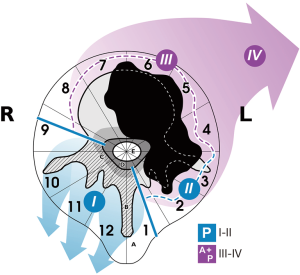

Type 7: This strategy came last in the author’s 25 years’ experience. It is indicated in thoracic and lumbar tumors which are growing anteriorly—even huge masses—in layer A without involvement of the canal (layer D) and without involvement of sectors 4 and 9 (Figure 7).

Conclusions

The decision-making process of spine tumor treatment and the planning of en bloc resection are matter of surgical oncology. Competence in orthopedic and/or neurosurgery are mandatory but secondary to a deep knowledge of tumor behavior. Further, multidisciplinary surgical skill is required, due to the axial spine location and to the requirement of a circumferential view: all organs and system can be case by case approached.

A deep knowledge of spine biomechanics is also needed for an appropriate 3D reconstruction, with particular consideration of sagittal alignment, very difficult to achieve in multilevel fusions, in order to avoid deformity, pain and instrumentation failures.

En bloc resection in the spine is therefore a very demanding surgical procedure, requiring oncological training and a team approach.

Indication and planning should follow some rules dictated by expert opinion and literature:

Diagnosis and staging must suggest that en bloc resection is the procedure of choice

Since 30 years the Enneking staging system has been adopted in many tumor centers and many reports and review confirm its validity. En bloc resection is “Enneking appropriate” for benign aggressive (stage 3) and for low grade malignant tumors (stage I). For high grade malignant tumor, en bloc resection is a valid option but must always be associated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy according to the sensitivity of the specific tumor. Isolated spine metastases in patient in good general status, if not sensitive to radio and chemotherapy, can be considered for en bloc resection.

A tumor-free margin en bloc resection can be safely performed with acceptable functional loss if tumor extension and surgical anatomy fulfill the criteria of feasibility

Seven groups of strategy to plan en bloc resection have been proposed to define the criteria of feasibility of this procedure according to tumor extension

Planning of the surgical procedure must consider the two previous points

The surgical approach or combination and timing of approaches must be decided combining the required oncological margins and the criteria of feasibility by tumor extension and by spine region.

If the margin is represented by relevant anatomical structures (dura, nerve roots, aorta, cava) a careful decision-making process will consider the improving of prognosis versus the functional loss. In this process the patient willing will be obviously relevant

Some details of surgical technique can reduce the complication rate and the morbidity

The morbidity profile of en bloc resections in the spine is high, due to the combination of the risks of anterior posterior spine surgery. Tumor surgery has also specific morbidity related to the need of dissecting through muscle and not through anatomical planes; further, en bloc resection require sacrificing not only the affected bone, but also almost all connecting elements creating a full instability.

Epidural bleeding should never be underestimated. Hemostasis is essential; poorly controlled epidural bleeding increases the risk of cardiovascular failure, post-operative hematoma, delayed wound healing, infection.

When the planning includes intralesional surgery or the risk of penetrating the tumor during resection is significant, selective arterial embolization is mandatory; however, when the surgeon anticipates a good probability of successful en bloc resection with oncological margins, tumor ischemia following embolization may induce peritumoral hyper-vascularization with increased risk of bleeding.

The final step of specimen removal must be planned to avoid tractions, torsions, shortening of the cord (19), particularly in multilevel resections (13). The effects on the cord vascularity during the tumor mass removal can be critical: it is one of the final step, after several hours of a bleeding surgery and the arterial pressure level should be kept still at a reasonable level to avoid the combination of stress and low blood flow.

The possibility that a single Adamkiewicz artery has the full responsibility of cord vascularity is controversial. Tomita and his group demonstrated on an animal model that the risk of cord ischemia is mostly related to the number of contiguous radicular arteries sacrificed rather that to a single artery (20). It can be recommended to cut no more than three nerve roots bilaterally in the thoracic spine, and avoid acute shortening or distraction during the resection.

Electrophysiological monitoring has a role to guide permanent arteries occlusion.

As an obvious consequence to the requirement of tumor-free margins, anatomical compartments are frequently disrupted, as in case of en bloc resection of a thoracic spine tumor involving layer A: at the end, no barriers will exist through the peridural space and both pleural cavity if both parietal pleurae have been resected with the tumor for margin purpose. As a consequence, the post-op hematoma will develop around the dura and inside both pleural cavities. A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage following unrepaired or incompletely repaired dural tear will develop as a transpleural CSF fistula, seldom evolving towards self-repair due to the negative pressure existing in the pleural cavity. Surgical repair of the dural tear, dura patch, or even major procedures like omentum flaps have been proposed for such an awful complication.

Previous surgery and previous RT increase the risk of complications related to dissection. Infection is particularly threatening, due to the compromised immune status of many of these patients. Late aortic dissection is reported mostly in multi operated cases including aorta release and submitted to monoportal high dose conventional RT. Mortality rate can be relevant, till 2.2% (16).

Non-union is not rare among late complications due to the hostile environment to solid bony fusion. Vascularized graft has been proposed for safe fusion.

Excellent results however can be obtained by circumferential reconstruction achieved by connecting the cage to the posterior systems and by the use of carbon fiber composite systems, biologically active in promoting bone formation.

Acknowledgements

The author is indebted with Carlo Piovani, for his invaluable work: he translated into original images the concepts of individual approach to en bloc spine resection.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Enneking WF. Muscoloskeletal Tumor Surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1983:69-122.

- Fisher CG, Saravanja DD, Dvorak MF, et al. Surgical management of primary bone tumors of the spine: validation of an approach to enhance cure and reduce local recurrence. Spine 2011;36:830-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosen G. Pre-operative (neo-adjuvant) chemotherapy for osteogenic sarcoma: a ten years experience. Orthopedics 1985;8:659-64. [PubMed]

- Xu N, Wei F, Liu X, et al. Reconstruction of the Upper Cervical Spine Using a Personalized 3D-Printed Vertebral Body in an Adolescent With Ewing Sarcoma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:E50-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colman MW, Karim SM, Lozano-Calderon SA, et al. Quality of life after en bloc resection of tumors in the mobile spine. Spine J 2015;15:1728-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roy-Camille R, Saillant G, Bisserié M, et al. Total excision of thoracic vertebrae (author's transl). Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 1981;67:421-30. [PubMed]

- Tomita K, Kawahara N, Baba H, et al. Total en bloc spondylectomy. A new surgical technique for primary malignant vertebral tumors. Spine 1997;22:324-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stener B, Johnsen OE. Complete removal of three vertebrae for giant-cell tumour. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1971;53:278-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Szava J, Maros T, Csugudeau K. Beitrage zur radiklen chirurgishen Behandlung der Wirbelneoplasmen und die Wiederherstellung del Wierbelshule nach einer Vertebrecktomie. Zentralblatt fur Chirurgie 1959;84:247-56. [PubMed]

- Biagini R, Casadei R, Boriani S, et al. En bloc vertebrectomy and dural resection for chordoma: a case report. Spine 2003;28:E368-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rhines LD, Fourney DR, Siadati A, et al. En bloc resection of multilevel cervical chordoma with C-2 involvement. Case report and description of operative technique. J Neurosurg Spine 2005;2:199-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murakami H, Tomita K, Kawahara N, et al. Complete segmental resection of the spine, including the spinal cord, for telangiectatic osteosarcoma: a report of 2 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:E117-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gösling T, Pichlmaier MA, Länger F, et al. Two-stage multilevel en bloc spondylectomy with resection and replacement of the aorta. Eur Spine J 2013;22 Suppl 3:S363-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gasbarrini A, Simoes CE, Amendola L, et al. Influence of a thread wire saw guide and spinal cord protector device in "en bloc" vertebrectomies. J Spinal Disord Tech 2012;25:E7-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah AA, Paulino Pereira NR, Pedlow FX, et al. Modified En Bloc Spondylectomy for Tumors of the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine: Surgical Technique and Outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:1476-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boriani S, Bandiera S, Donthineni R, et al. Morbidity of en bloc resections in the spine. Eur Spine J 2010;19:231-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boriani S, Weinstein JN, Biagini R. Primary bone tumors of the spine. Terminology and surgical staging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:1036-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan P, Boriani S, Fourney DR, et al. An assessment of the reliability of the Enneking and Weinstein-Boriani-Biagini classifications for staging of primary spinal tumors by the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:384-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawahara N, Tomita K, Kobayashi T, et al. Influence of acute shortening on the spinal cord: an experimental study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:613-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ueda Y, Kawahara N, Tomita K, et al. Influence on spinal cord blood flow and function by interruption of bilateral segmental arteries at up to three levels: experimental study in dogs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:2239-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]