Establishing a common language for lumbar transforaminal epidural steroid injections

Introduction

The process of ordering lumbar transforaminal epidural steroid injections (LTFESIs) can create confusion between spine surgeons and pain management physicians. Unlike the cervical spine, a lumbar paracentral disc herniation, lateral recess stenosis, or central pathology can affect the traversing nerve root at a given level. For example, an L4/L5 right-sided paracentral disc herniation would affect the right L5 nerve root. The pain management physician would inject into the right L5 foramina at the L5/S1 level to target this pathology. However, perhaps because a surgeon would perform a microdiscectomy at the L4/L5 level for this pathology, the surgeon may be inadvertently prone to order an L4/L5 injection. To eliminate this confusion, we propose that instead of ordering a lumbar injection at a given level, the injection is simply ordered to address a specific nerve root with a specified laterality (ex. right L5 nerve root). This is significant because it has the potential to eliminate wrong-site procedures and improve patient safety, communication, and positive outcomes.

Despite a growing number of spinal injection procedures, there exists a paucity of evidence on wrong-site injections. A 2010 analysis identified 13 cases or wrong-site injections out of roughly 49,000 pain management procedures, five of which were transforaminal epidural steroid injections (1). The authors identified multiple lapses of universal protocol in most cases. However, these cases were identified by reviewing quality improvement records. As such, it is likely that these are under-reported. Additionally, it is unclear if an injection would be identified as wrong-site if it was consistent with the injection order, despite the order being incorrect. To our knowledge, there is no such study specifically analyzing the communication and ordering process for spinal injections initiated by the spine surgeon and inconsistencies in ordering patterns.

The purpose of this study is to analyze the ordering process and language of LTFESIs with the main objective of proposing a common language between spine surgeons and pain management physicians for ordering LTFESIs.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jss-21-71).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of prospectively collected data of 60 patients at a single, private, orthopaedic spine practice under the care of spine surgeons or physician assistants over a 1-year period. Patients with missing documentation and younger than age 18 were excluded. Demographics can be found in Table 1. The progress note, injection order form, procedure note, and procedural fluoroscopy were reviewed. Procedural fluoroscopic images were reviewed by the primary author of this paper and vertebral levels were counted using the methods described in Spinal Deformity Study Group’s radiographic measurement manual (2). If there were inconsistencies between one or more of these steps, it was deemed a failure (Table 2). Failures were then categorized into subtypes to differentiate whether the discrepancies were found in the taxonomy used between the ordering physician’s intended injection level as described in previous office visit documentation versus the injection order itself, the injection order versus the flouroscopic imaging, or procedure note in comparison to the fluoroscopic imaging.

Table 1

| Variables | Failure | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N=60) | Yes (n=37) | No (n=23) | ||

| Age (in years) at injection, median (IQR) | 59 (45.5, 70.5) | 62 (48, 72) | 54 (37, 68) | 0.181 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 28.5 (24, 34) | 28 (26, 34) | 29 (22, 34) | 0.648 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.920 | |||

| Female | 37 (61.7) | 23 (62.2) | 14 (60.9) | |

| Male | 23 (38.3) | 14 (37.8) | 9 (39.1) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.357 | |||

| White | 39 (65.0) | 22 (59.5) | 17 (73.9) | |

| Black, African American | 17 (28.3) | 13 (35.1) | 4 (17.4) | |

| Declined/unknown | 4 (6.7) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | >0.99 | |||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 49 (81.7) | 30 (81.1) | 19 (82.6) | |

| Declined | 6 (10.0) | 4 (10.8) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 (8.3) | 3 (8.1) | 2 (8.7) | |

Table 2

| Method of failure | Failure (total n=60) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=37) | Overall | Failures | |

| Taxonomy* | 17 | 28.30% | 45.90% |

| Order vs. image# | 18 | 30.00% | 48.60% |

| Procedure note vs. image& | 8 | 13.30% | 21.60% |

*, taxonomy discrepancy between the original plan outlined in the ordering physician’s note versus the injection order form; #, differences in the level written on the Injection order form versus the level seen on intra-operative fluoroscopy; &, discrepancies between the procedural note available after epidural steroid injection versus the level seen on intra-operative fluoroscopy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was then performed by the lead author to assess for any differences in outcomes between the groups and significance of the findings. We calculated our sample size prior to the study and powered it at 90%; Descriptive statistics, Chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t-test, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used where appropriate utilizing SAS v9.4. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolves.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by ethics board of OrthoCarolina Research Institute (IRB#01-21-03E) and individual consent for this retrospective study was waived.

Results

Thirty seven out of sixty encounters (61.6%) were considered a failure (Table S1). A breakdown of the order and outcome associated with failure can be found in Table 3. Additionally, a further analysis of the different modes of failure can be seen in Table 2. There were no failures when ordering an S1 nerve root injection. We identified one wrong-site procedure (laterality) and one wrong-level order that was identified and corrected by the interventionalist. There was a higher rate of failure if the injection was ordered by a mid-level provider versus a physician (P=0.009) (Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences noted in patient outcomes regarding provoked pain during the procedure or complications.

Table 3

| Physician orders and patient outcomes | Failure | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=60) | Yes (n=37) | No (n=23) | ||

| Order description, n (%) | 0.766 | |||

| Ordered at level | 40 (66.7) | 26 (70.3) | 14 (60.9) | |

| Ordered at nerve root | 15 (25.0) | 8 (21.6) | 7 (30.4) | |

| Ordered at level and nerve root | 5 (8.3) | 3 (8.1) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Outcome, n (%) | 0.822 | |||

| Provoked pain | 54 (90.0) | 34 (91.9) | 20 (87.0) | |

| No effect | 4 (6.7) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (8.7) | |

| No complications | 2 (3.3) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (4.3) | |

Table 4

| Diagnosis and description of prior surgical procedures | Failure | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=60) | Yes (n=37) | No (n=23) | ||

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.994 | |||

| Lumbar radiculopathy | 33 (55.0) | 20 (54.1) | 13 (56.5) | |

| Low back pain | 7 (11.7) | 4 (10.8) | 3 (13.0) | |

| Spinal stenosis | 5 (8.3) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (13.0) | |

| Lumbar disc herniation | 5 (8.3) | 3 (8.1) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Lumbar degenerative disc disease | 2 (3.3) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (4.3) | |

| None | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lumbar radiculopathy | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lumbar radiculopathy and spinal stenosis | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lumbar stenosis | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | |

| Right L4/5 and left L5/S1 | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lumbar disc herniation and lumbar radiculopathy | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Spondylolisthesis | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Lumbar degenerative disc disease, spinal stenosis | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Prior surgery, n (%) | 0.137 | |||

| No | 46 (76.7) | 26 (70.3) | 20 (87.0) | |

| Yes | 14 (23.3) | 11 (29.7) | 3 (13.0) | |

| If yes, describe, n (%) | >0.99 | |||

| Left L3/L4 far lateral microdiscectomy | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| X stop L4/L5 and L5/S1 | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Left L5/S1 decompression | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | |

| Right L5/S1 laminotomy | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | |

| Left L5/S1 laminotomy with microdiscectomy | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.3) | |

| L4/5 instrumented fusion | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Right L5/S1 hemilaminectomy | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| L4/L5 microdiscectomy | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Left L5/S1 mircordisc | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| L4/S1 decompression and fusion | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Left L5/S1 microdiscectomy | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| L4/L5 decompression and fusion and L5/S1 lumbar spine surgery (not specified) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| L5/S1 decompression and fusion | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Side, n (%) | 0.867 | |||

| Right | 32 (53.3) | 20 (54.1) | 12 (52.2) | |

| Left | 20 (33.3) | 13 (35.1) | 7 (30.4) | |

| Bilateral | 8 (13.3) | 4 (10.8) | 4 (17.4) | |

| Ordering provider type, n (%) | 0.009 | |||

| Pa | 40 (66.7) | 20 (54.1) | 20 (87.0) | |

| Attending | 20 (33.3) | 17 (45.9) | 3 (13.0) | |

Discussion

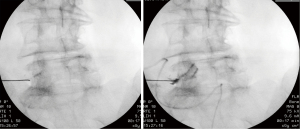

There were no inconsistencies in ordering an S1 injection, likely because this injection could only be ordered at the nerve root (Figure 1). Fortunately, no additional complications were noted in patients who had a failure versus those without. Although not intended, there may also be a diffuse effect of the LTFESI that may provide relief even in the setting of a wrong-site procedure. The most common method of failure was differences in the injection order form and the level notated by the intra-operative fluoroscopy as seen in Figures 2,3. Next most common error was differences in language used in the ordering physician’s plan and the injection order form itself. Overall, significant variation is seen throughout the charting process and this is likely attributing to the high volume of deemed failures. Additionally, one obstacle to implementing a common LTFESI language is the fact that some insurers require notating a level (ex. L4/L5) for approval.

Lastly, it is critical to utilize and save a localization film to ensure accuracy and accountability. The interventionalist plays an important role in ensuring the accuracy of orders and correlating patient imaging with the intended injection site. To attempt to prevent medical errors, the World Health Organization’s Surgical Safety Checklist includes a component regarding displaying pertinent imaging during procedures (3). Another critical checkpoint not discussed in the literature is in the case of the interventionalist evaluates the patient and imaging for him/herself and decides to inject at a different site than originally received from the referring physician. This factor could lead to intentional targeting of an adjacent nerve root and although deemed as a failure in our study, is in fact not a medical error but rather a part of the medical decision making process. Reasons for changing injection levels could include variations in symptomatology of the patient or anatomic structures visible on MRI that restrict injection such as osteophyte formation or worsening foraminal stenosis.

Limitations

This is a single center study with inherent limitations due to its retrospective design. For example, it does not take into account if other practices are already using this nomenclature. There is also subjectivity in defining a failure as no strict definition exists beyond a wrong-site procedure. Furthermore, we did not review any imaging data except for the procedural fluoroscopy. Additionally, procedural fluoroscopy was not cross referenced with lumbar MRI imaging. Additionally, full body spinal imaging was not available for review. This does not allow for identification of lumbar sacralization and therefore does not ensure we accurately nor consistently numbered the vertebral bodies in comparison to the previous reviewers (4). Lastly, there was no patient follow-up beyond the date of the initial injection.

Conclusions

There were multiple inconsistencies identified at various steps in the injection ordering process. This study also suggests a significantly higher incidence of wrong-site and near-miss procedures than previously reported. This indicates a need to standardize the language used in this process to avoid wrong-site procedures, as well as provide education to those involved in the ordering process. We propose indicating the affected nerve root in all cases rather than the level of disc pathology to avoid confusion. For example, the surgeon would indicate the left L5 nerve root instead of notating a left L5/S1 injection on an order form. The one near-miss procedure in this study may have been prevented if this was implemented. Beyond this direct application of semantics regarding ordering of a nerve root injection, the idea behind standardization of certain medical practices is the foundation to preventing medical errors. By standardizing this process, we can enable more providers to work together towards better patient care and error prevention. Further studies are necessary to assess the effectiveness of updating injection order forms to reflect this new nomenclature.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by OrthoCarolina Research Institute (OCRI).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jss-21-71

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jss-21-71

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jss-21-71). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolves. The study was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by ethics board of OrthoCarolina Research Institute (IRB#01-21-03E) and individual consent for this retrospective study was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Cohen SP, Hayek SM, Datta S, et al. Incidence and root cause analysis of wrong-site pain management procedures: a multicenter study. Anesthesiology 2010;112:711-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O’Brien MF, Kiklo T, Blanke KM, et al. (editors). Radiographic measurement manual. Memphi, USA: Medtronic Sofamor Danek Inc., 2008.

- Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 2009;360:491-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lian J, Levine N, Cho W. A review of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae and associated vertebral numeration. Eur Spine J 2018;27:995-1004. [Crossref] [PubMed]