The utilization of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy in recurrent lumbar disc herniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Highlight box

Key findings

• Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (PELD) is safe, effective treatment for recurrent herniated discs but it is unclear whether it is superior to other minimally invasive options.

What is known and what is new?

• PELD is safe for management of recurrent herniated disc.

• This manuscript examines the utility of PELD in comparison to other surgical options.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• PELD should be incorporated into the clinical management of recurrent herniated discs and further research is needed to compare the minimally invasive surgical options to determine a superior approach. Clinical judgment is required to select between surgical options at this time.

Introduction

Spine anatomy

The spine consists of 33 vertebrae divided as follows: 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 3 to 5 fused vertebrae in the coccyx. Each level contains a central column (vertebral canal) through which the spinal cord travels, foramen through which nerve roots exit from the spinal cord, and a vertebral body which is separated by discs (1). Each disc contains a nucleus pulposus that is contained within the anulus fibrosus, which is a thick collagenous ring. The disc can herniate, which involves extrusion of contents of the nucleus pulposus through the anulus fibrosus, and this can cause back pain as well as pain or neurological deficit in a dermatomal pattern if a nerve root is impinged, or can compress the central cord itself in certain circumstances. The most common location for disc herniation is the lumbar spine (2-4).

Management of herniated disc

The mainstay of initial treatment for herniated disc is conservative measures, which can include pain medications, physical therapy, and injection, which can include translaminar/transforaminal (TF) epidural steroid injections or selective nerve root blocks (2,3). For those who fail conservative treatment or those who have neurological impairment, surgical management is recommended. The gold standard surgical treatment is microdiscectomy.

Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (PELD)

A novel approach to the spine was invented by Yeung et al. (5) and Hoogland et al. (6) known as the Yeung endoscopic spine system (YESS) and transforaminal endoscopic spine system (TESSYS) techniques respectively. This led to the development of the TF and interlaminar (IL) approach to the spine (7). Both systems can be utilized to perform surgical discectomy for management of a lumbar disc herniation (LDH) and offer the advantage of less blood loss and quicker recovery time compared to other surgical discectomy techniques. The endoscopic approach for management of LDH is well established as a safe, effective procedure. However, a known complication of various surgical procedures to manage LDH is that the herniation can recur (R-LDH). The rate of recurrence varies between study and type of surgery utilized, but generally falls between 5% and 15% (7,8). Implicated risk factors in R-LDH include smoking, disc protrusion, and diabetes (8). The use of PELD with either the TF or IL approach at this juncture of R-LDH has not been well studied. In the context of revision surgery, it is often more challenging due to epidural fibrosis and scarring (8). The TF approach allows for a direct approach to the herniated disc via the neuroforamen without dissecting the ligamentum flavum or retracting any nerve root. However, the IL approach allows for better approach for intracanalicular disc herniation or sequestered disc herniation (9).

Advantages and disadvantages of PELD

The advantage of utilizing PELD is that it is currently the most minimally invasive method to surgically intervene on the spine. Meanwhile, the majority of discectomies are done with the traditional “open” method, which requires retraction of paravertebral muscles, removal of spinal lamina, and facet joint removal. This can cause scarring and instability of the spine, with 10% or more of patients having residual symptoms (10). The theoretical advantages of PELD are numerous, but include that the procedure can be done under local anesthesia with less anesthesia related risks, smaller incision, and less trauma to the spine leading to less instability (10). Minimally invasive Trans lumbar interbody fusion (MIS-TLIF) is another minimally invasive technique that can manage R-LDH that is typically recommended when there is an associated instability in the spine. However, MIS-TLIF also cannot be performed under sedation and this prohibits early mobilization of the patient. Additionally, PELD can retain the motor segment and decrease the incidence of fusion disease such as adjacent segment disease (11). The existing literature does state that the disadvantage of PELD compared to MIS-TLIF is a higher recurrence rate of disc herniation (11). Microendoscopic discectomy (MED) is another minimally invasive surgical technique which utilizes tubular retractors and microscope and is associated with smaller incision, less blood loss, and shorter recovery time than open lumbar microdiscectomy (OLM) (12). MED can be performed with general anesthesia or local anesthesia with or without an epidural (13). A disadvantage of PELD is that it has arguably a steeper learning curve than the other minimally invasive modalities described above. Therefore, the question that is posed at this juncture is whether PELD is an effective treatment despite the smaller operating window, and whether it is a superior treatment modality despite the steeper learning curve.

The purpose of this systematic review is to determine the effectiveness and safety of PELD with either approach in management of R-LDH, and compare PELD to other surgical interventions. We present this article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://jss.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jss-24-47/rc).

Methods

Search strategy and data sources

We searched the PUBMED, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases with the query “((endoscopic spine surgery) OR (endoscopic spinal surgery) OR (percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy) OR (percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar discectomy) OR (percutaneous endoscopic transforaminal discectomy) OR (PEID) OR (PELD) OR (PETD)) AND ((recurrent) OR (revision)) AND ((lumbar disc herniation) OR (lumbar disk herniation)) OR (rLDH)” on 5/20/2024. Search strategy and results are in Appendix 1. Inclusion criteria was defined as follows: lumbar revision surgery for recurrent herniated disc, greater than or equal to 10 patients, either the use of TF or IL approach to the spine, and article written in English or English translation provided by journal. Exclusion criteria was defined as follows: systematic review papers, published abstracts without full text article, adolescent patient population, surgery performed for an indication other than R-LDH. A recurrent herniated disc was defined as a herniated disc located at the same level as a prior herniated disc at any point of time that was confirmed with imaging findings. A re-recurrent herniated disc was defined as a third occurrence of herniated disc at the same level as the prior two occurrences with confirmative imaging findings.

Study selection

One physician reviewer (S.R.) examined all titles and abstracts, as well as full texts to determine eligibility for inclusion in the study. If it was unclear whether to include a study, a second reviewer and content expert (S.K.) was contacted for clarification.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data from each study was extracted to Microsoft Excel using a data collection form. The primary outcome of interest was visual analog scale (VAS) score and Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) of pain in the back as well as leg before and after surgery. A secondary outcome of interest was Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores before and after surgery. Other outcomes of interest included complication rates, as well as re-recurrence rate of disc herniation. Re-recurrence of herniated disc was defined as a third occurrence of herniated disc at the same level as the initial herniated disc confirmed by imaging at any point of time after surgical management of the initial recurrent disk (second occurrence). Risk of bias assessment was performed for each study. For retrospective cohort studies, the Cochrane “Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Cohort Studies” was utilized (14). For case series studies, the Modified Delphi Questionnaire was utilized (15). For randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) was utilized (16).

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

If a study had both a PELD arm and non-PELD arm, only data from the endoscopic spine arm was extracted for statistical analysis, with the exception of meta-analysis as described below. If a study compared two arms of endoscopic spine, then both arms were included in statistical analysis.

VAS and NRS scores were combined for pooled analysis as both systems measure pain on a scale of 0–10. VAS and NRS scores were analyzed for both pre- and post-operation for both leg and back. The analysis utilized a weighted average based on number of discs operated on and the reported average VAS or NRS score for back and leg respectively in each study. If a study did not report VAS or NRS scores both pre- and post-operatively it was excluded from this analysis. For ODI, only classical ODI score was utilized and a weighted average was taken based on number of discs operated on and the average ODI prior to surgery, as well as ODI after surgery. If a study did not report ODI score or it utilized an alternate ODI such as Korean-ODI, it was excluded from this analysis. Additionally, if a study reported VAS, NRS, or ODI scores but they appeared to be outside the range of traditional VAS, NRS, or ODI scores, or ODI was reported as a percentage and the range of possible score was not reported, it was excluded from this weighted average.

Meta-analysis

Single-arm meta-analyses were performed for all studies reporting data on PELD. Meta-analyses were also performed if at least two studies compared PELD to another surgical modality. All meta-analytic results were analyzed using Stata 17 (17). For studies reporting pre- and post-values for VAS, NRS, or ODI scores, we calculated standard deviation from change scores using the following formula:

The correlation coefficient was assumed as 0.5 as a conservative measure. As for dichotomous outcomes (e.g., re-recurrence rate), we calculated standard error as p*(1 − p)/n where ‘p’ is the proportion of events and ‘n’ is the sample size. For instances where ‘p’ = 0, we use the Mantel-Haenszel correction where 0.5 is added to both the numerator and denominator. Meta-analytic results were checked for publication bias via sensitivity analysis (e.g., examining the effect size after removing or imputing studies) and funnel plots.

Results

A total of 614 non-duplicate articles were identified in the initial search, of which 32 articles were included after title/abstract screen, and 20 articles were included after full text screen (Figure 1) (9,18-36).

Study characteristics

The characteristics of these 20 studies are depicted in Table 1. Of these 20 articles, 11 studies (55%) were cohort, 1 study (5%) was a RCT, 8 studies (40%) were case-series. Of note, the articles originated primarily from Asian countries, as well as 1 study from Germany and 1 study from Greece. There were no studies from North America, which is the location of the authors of this paper. Across the 20 studies, a variety of interventions were utilized in the initial surgery (prior to recurrence) including endoscopic spine, MED, and open discectomy. Additionally, the 20 studies have similar definitions for R-LDH, however, the duration from symptomatic return to procedure (i.e., duration of conservative management) varied across the 20 studies. For the revision surgery, 11 studies (55%) utilized only TF approach, 3 studies (15%) utilized only IL approach, and 6 studies (30%) utilized both approaches.

Table 1

| Study | Country/region of origin | TF or IL approach | Initial surgery | Comparison | Study design | Spinal levels operated on | Duration of follow-up (months) | Definition of recurrence/inclusion criteria | Outcome measurement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (endoscopic) | Total | L4–5 | L5–S1 | Other | |||||||||

| Yuan Yao, 2017 (35) | China | TF | PELD | MIS-TLIF, MED | Retrospective cohort study | 28 | 28 | 19 | 9 | 0 | 12 | (I) The patient met the criteria for PELD recurrence (i.e., the patient had undergone a successful PELD as confirmed by a pain-free period of at least 1 month, there were recurrent symptoms of pain, and a magnetic resonance imaging scan confirmation of a reherniated fragment on the same level as the previous PELD surgery was achieved); (II) conservative therapy failed to relieve the recurrent pain | VAS back, VAS leg, ODI, SF12-PCS, SF12-MCS |

| Yuan Yao, 2017 (36) | China | TF | MED | MIS-TLIF | Retrospective cohort study | 47 | 47 | 20 | 27 | 0 | 12 | The MED recurrence was defined as follows: (I) patients underwent a successful MED surgery that could be confirmed by a pain-free interval of at least 1 month; and (II) recurrent pain symptoms and MRI confirmation of the recurrent herniation at the same level as that in the previous MED surgery | VAS back, VAS leg, ODI, SF12-PCS, SF12-MCS |

| Chao Liu, 2017 (29) | China | TF | Discectomy | MIS-TLIF | Prospective cohort study | 209 | 209 | 127 | 82 | 0 | 46.5 (mean) | (I) At least 6 months of pain relief after primary lumbar disk surgery; (II) presence of recurrent radicular pain unresponsive to conservative treatment for at least 6 weeks; and (III) magnetic resonance imaging on lumbosacral spine showing disk herniation at the same level of the primary diskectomy | JOA score, ODI score, VAS back, VAS leg, satisfaction rate, recovery rate |

| Sebastien Ruetten, 2009 (31) | Germany | Both | Discectomy | MED | Randomized controlled trial | 50 | 50 | 24 | 17 | 9 | 24 | Patients were enrolled who had undergone previous conventional discectomy, presented with acute occurrence of radicular leg symptoms on the same side after a pain free interval and who showed a recurrent disc herniation in the same level in a magnetic resonance imaging with contrast medium | VAS back, VAS leg, ODI, NASS |

| Jung-Sup Lee, 2018 (27) | Korea | TF | OLM | OLM | Retrospective cohort study | 35 | 35 | 27 | 0 | 8 | 29.7 (mean) | (I) Patients who previously received an OLM due to lumbar disk herniation; (II) had radicular pain after being pain free for 6 months; (III) a soft disk located at paracentral; (IV) with the source of pain a recurrent lumbar disk herniation at the same area as the previous surgery, as confirmed through MRI; (V) and did not respond to conservative treatment | VAS back, VAS leg, ODI |

| Chi Heon Kim, 2012 (24) | Korea | IL | Open discectomy | None | Retrospective case-series study | 10 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 14.4 (mean) | The indications of surgery were recurrent pain that had not subsided with nonsurgical management for at least 6 weeks in all but one patient and the presence of soft disk reherniation at the previous operation site in subsequent MR images and computed tomography scans | VAS back, VAS leg, Korean-ODI, Macnab criteria |

| Koichi Yoshikane, 2021 (9) | Japan | Both | Various | IL vs. TF | Retrospective cohort study | 49 | 52 | 29 | 13 | 10 | 18.6 (mean) | The indications for FELD-IL were as follows: (I) intracanalicular disc herniation at L5/S1; and (II) intracanalicular sequestrated disc herniation located at L4/5 level or higher. The indications of FELD-TF were as follows: (I) lesion is located at L4/5 level or higher; and (II) bulging, subligamentous, or transligamentous extruded disc herniation at the disc level | JOABPEQ, NRS scale for back pain, lower limb pain, and lower limb numbness |

| Gang Xu, 2023 (34) | China | TF | Discectomy | None | Retrospective case-series study | 31 | 31 | 24 | 6 | 1 | 24 | (I) Recurrence of lower-extremity leg radiating pain after the initial surgery; (II) relief of symptoms for more than 1 month after the initial surgery; (III) confirmation by CT, MRI, or other imaging techniques that the herniated nucleus pulposus oppressed the corresponding nerve root, which was clinically consistent with the clinical symptoms and physical examination; (IV) no significant alleviation in symptoms after conservative treatment; and (V) voluntary participation and cooperation with the follow-up | VAS, JOA, modified Macnab criteria |

| YunHee Choi, 2020 (19) | Korea | Both | Endoscopic, open discectomy | Primary LDH | Prospective cohort study | 33 | 33 | 18 | 15 | 0 | 24 | We selected patients according to the following inclusion criteria: (I) single-level LDH or recurrent LDH at L4–5 or L5–S1; (II) age ≤60 years; (III) symptomatic primary LDH or recurrent LDH verified with magnetic resonance imaging; (IV) previous history of open discectomy for patients with recurrent LDH; (V) absence of spinal stenosis at any level; (VI) absence of a psychiatric or neuromuscular diagnosis, such as depression or Parkinson disease; and (VII) a follow-up period longer than 6 months | VAS back, VAS leg, Korean-ODI |

| Thomas Hoogland, 2008 (21) | Germany | TF | Microscopic disc surgery, ESS | None | Retrospective case-series | 262 (238 completed 2-year follow-up) | 262 | 137 | 113 | 12 | 24 | Recurrences that developed as a new lumbar disc herniation with at least a 6-month pain-free interval at the same level | VAS back, VAS leg, Macnab criteria |

| Shifeng Jiang, 2021 (22) | China | TF | Laminectomy | Laminectomy | Retrospective cohort study | 24 | 24 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 12 | (I) Patients with single-segment lumbar disc herniation, who had undergone traditional laminectomy; (II) patients who experienced pain relief for more than 6 months after the first surgery; (III) those who have underwent strict conservative treatment for more than 3 months, but with no obvious effect; (IV) those who experienced weakening muscle strength and a feeling of numbness in the innervation area caused by the last lumbar disc herniation; and (V) those whereby CT, MRI and other imaging examinations showed that the R-LDH was in the same segment | VAS, ODI |

| Chi Heon Kim, 2014 (25) | Korea | Both | Various | None | Retrospective case-series | 26 | 26 | 15 | 8 | 3 | Unclear | Recurrent predominant leg pain irrespective of nonsurgical management for at least 6 weeks excluding severe intractable pain or accompanying weakness, and the presence of soft disk re-herniation at the previous operation site in subsequent MR images and computed tomography scans | VAS, Korean ODI |

| Dong Yeob Lee, 2009 (26) | Korea | TF | OLM | OLM | Retrospective cohort study | 25 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 34 (mean) | (I) A previous episode of OLM at L4–5 level resulting from lumbar disc herniation; (II) recurrent radicular pain after a pain-free interval longer than 4 weeks; (III) recurrent disc herniation at the same level and the same side, verified by radiological studies (i.e., the presence of abnormal epidural tissue that did not enhance after contrast injection, as well as epidural fibrosis showing enhancement with gadolinium on T1-weighted MRI); and (IV) failure of extensive conservative treatment for more than 6 weeks | VAS, ODI |

| Antao Lin, 2024 (28) | China | Both | PELD | IL vs. TF | Retrospective cohort study | 96 | 96 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 12 | (I) The patient had been treated with PETD for LDH in the L4/5. Low back pain and lower extremity symptoms are significantly relieved after the initial surgery, and the pain is relieved for more than 2 weeks after the surgery. (II) MRI of lumbar spine after the initial operation showed that the herniated disc had been completely removed. (III) Low back pain and lower extremity neurologic symptoms reappeared again, and CT and MR findings of the lumbar spine were consistent with clinical symptoms and confirmed recurrent LDH (L4/5). (IV) Patients failed to respond to conservative treatment (≥2 months) | VAS, ODI, JOA |

| Keng-Chang Liu, 2020 (30) | Taiwan | IL | Open discectomy | None | Case-series | 24 | 24 | 8 | 16 | 0 | 24 | (I) Recurrent leg radiation pain that failed at least 3 months of conservative treatment excluding severe intractable pain or accompanying motor weakness, (II) R-LDH was confirmed by MRI, and (III) MRI findings were correlated with clinical symptoms and signs | VAS back, VAS leg, ODI |

| Kyung Hyun Shin, 2011 (32) | Korea | Both | Open discectomy | None | Case-series | 41 | 41 | 26 | 13 | 2 | 16 (mean) | Indications for surgery were (I) intractable pain that had not responded to conservative management over 6 weeks and (II) recurrent disc herniation with compression of nerve root confirmed by MRI | VAS back, VAS leg, Modified Macnab criteria |

| Anqi Wang, 2020 (33) | China | TF | PELD | MIS-TLIF | Retrospective cohort study | 24 | 24 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 12 | Patients who (I) had at least a one-month pain-free interval after the primary PELD; (II) showed recurrent pain symptoms, and a herniated disc fragment on the same level as that in the previous PELD, confirmed by MRI; and (III) conservative therapy failed to relieve the recurrent pain. In addition, to avoid scar formation from real R-LDH, only patients showing the following were enrolled: (I) definite neurological symptom; (II) space-occupying lesions in the lumbar spinal canal that were confirmed by MRI; (III) a herniation of the nucleus pulposus was observed intraoperatively | VAS back, VAS leg, ODI |

| Stylianos Kapetanakis, 2019 (23) | Greece | TF | Microdiscectomy | None | Case-series | 45 | 45 | 26 | 11 | 8 | 12 | (I) Radiculopathy; (II) positive nerve root tension sign; (III) negative prone instability test; (IV) motor neurologic deficit on clinical examination; (V) hernia confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine, in compliance with clinical findings; (VI) emergence of resistant to 12-week conservative treatment (medication regimen, physical therapy sessions and epidural spinal injections) pain | VAS back, VAS leg, Short-Form 36 |

| Yong Ahn, 2004 (18) | Korea | TF | Open discectomy | None | Case-series | 43 | 43 | 35 | 6 | 2 | 12 | (I) A previous episode of conventional open discectomy resulting from lumbar disc herniation; (II) recurrent radicular pain after a pain-free interval longer than 6 months; (III) recurrent disc herniation at the same level, regardless of the side, verified by the radiologic studies; and (IV) failure of extensive conservative therapies | VAS, MacNab criteria |

| Burcu Goker, 2020 (20) | Turkey | IL | IL endoscopic surgery or microdiscectomy | IL endoscopic surgery after MED vs. IL | Retrospective cohort study | 60 | 60 | 26 | 28 | 6 | 36 | The indication for surgery was defined according to present-day standards based on radicular pain symptoms, existing neurologic deficits, and current lumbar MRI findings. The onset of pain from the time of operation ranged from 5 days to 3 months (mean =39 days). Twenty patients received conservative treatment for 2 weeks on average from the onset of pain. The duration from the initial surgery to revisional surgery was 28 months on average (5 days to 41 months) | VAS back and leg, ODI |

| Total | 1,162 | 1,165 | 714 (61.3%) | 389 (33.4%) | 62 (5.3%) | ||||||||

MIS-TLIF, minimally invasive translumbar interbody fusion; MED, microendoscopic discectomy; VAS, visual analog scale; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; SF12-PCS, Short Form Physical Component Score; SF12-MCS, Short Form Mental Component Score; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; JOA, Japanese Orthopedic Association; NASS, North American Spine Society Instrument; OLM, open lumbar microdiscectomy; FELD, full endoscopic lumbar discectomy; JOABPEQ, Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; CT, computed tomography; LDH, lumbar disc herniation; ESS, endoscopic spine surgery; TF, transforaminal; IL, interlaminar; R-LDH, recurrence lumbar disc herniation; MR, magnetic resonance; PELD, percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy.

VAS/NRS, and ODI outcomes

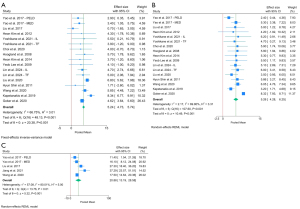

The VAS/NRS and ODI outcomes of studies are depicted in Table 2. Table 1 shows a total of 1,162 patients and 1,165 discs operated on. 714 (61.3%) surgeries were at level L4–5, 390 (33.4%) surgeries were at level L5–S1, and 62 (5.32%) surgeries were at other lumbar levels. Fifteen studies reported average VAS scores or NRS of back and leg pain. Pooled weighted averages illustrated a 5.24-point improvement in VAS back scores (Figure 2A) and a similar 5.26-point improvement in VAS leg scores (Figure 2B). ODI was reported in 5 studies with a pooled weighted average ODI showing an improvement of 20.88 units (Figure 2C). Five studies reported confirming successful surgery with post-operative imaging.

Table 2

| Study No. | First author | Country/region of origin | VAS/NRS back | VAS/NRS leg | ODI | Operative time, min | Radiological efficacy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-op | Post-op | Improvement | Pre-op | Pre-op | Improvement | Pre-op | Post-op | Improvement | |||||||

| 1 | Yuan Yao | China | 5.9 (1.1) | 3 (1.5) | 2.9 (1.3)* | 7.2 (1) | 4.8 (1) | 2.4 (1.0)* | 27.7 (4.7) | 16.3 (5.3) | 11.4 (5.03)* | 75 (31.6) | Not reported | ||

| 2 | Yuan Yao | China | 5.9 (1.3) | 2.5 (1) | 3.4 (1.2)* | 7.1 (1.1) | 1.8 (0.8) | 5.3 (0.98)* | 28.6 (4.7) | 12.5 (2.3) | 16.1 (4.07)* | 63.4 (20.3) | Not reported | ||

| 3 | Chao Liu | China | 3.8 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.2) | 0.7 (1.2) | 6.1 (2.2) | 1.1 (0.8) | 5 (1.93)* | 38.7 (5.2) | 11.4 (3.2) | 27.3 (4.54)* | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 4 | Sebastien Ruetten | Germany | Excluded due to improper range | Excluded due to improper range | – | Excluded due to improper range | Excluded due to improper range | – | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 5 | Jung-Sup Lee | Korea | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 6 | Chi Heon Kim | Korea | 8 (2.1) | 3.7 (3.6) | 4.3 (3.1) | 8.3 (1.9) | 4.1 (3.6) | 4.2 (3.12) | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Present | ||

| 7—TF | Koichi Yoshikane | Japan | 7.3 (2.4) | 3.4 (2.8) | 3.9 (2.6) | 8 (1.9) | 3.3 (2.5) | 4.7 (2.26)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | 31.7 (12.7) | Present | ||

| 7—IL | Koichi Yoshikane | Japan | 7 (3.0) | 1.5 (2.4) | 5.5 (2.7) | 8.6 (1.3) | 2.4 (3.1) | 6.2 (2.7)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | 33 (16.5) | Present | ||

| 8 | Gang Xu | China | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 9 | YunHee Choi | Korea | 6.1 (2.4) | 2.1 (2.4) | 4 (2.4) | 7.5 (1.6) | 1.6 (2.4) | 5.9 (2.12)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 10 | Thomas Hoogland | Germany | 8.6 (1.49) | 2.9 (2.21) | 5.7 (2)* | 8.5 (1.62) | 2.6 (2.27) | 5.9 (2.02)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Present | ||

| 11 | Shifeng Jiang | China | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | – | 39.9 (7.65) | 2.61 (1.55) | 37.29 (7.00)* | 65.3 (12.5) | Not reported | ||

| 12 | Chi Heon Kim | Korea | 6.6 (2.6) | 2.9 (2.3) | 3.7 (2.5) | 7.8 (1.8) | 2.5 (2.6) | 5.3 (2.31)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 13 | Dong Yeob Lee | Korea | 7 (2.8) | 2.9 (2.4) | 4.1 (2.6) | 8.4 (1.7) | 2.9 (2.5) | 5.5 (2.21)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | 45.8 (11.1) | Present | ||

| 14—TF | Antao Lin | China | 6.2 (1.7) | 1.2 (0.7) | 5 (1.5)* | 6.9 (1.5) | 0.9 (0.5) | 6 (1.32)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | 81.3 (7.4) | Not reported | ||

| 14—IL | Antao Lin | China | 5.6 (1.2) | 0.9 (0.5) | 4.7 (1)* | 6.1 (1.3) | 1 (0.7) | 5.1 (1.13)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | 60.2 (7.9) | Not reported | ||

| 15 | Keng-Chang Liu | Taiwan | 8.5 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.66) | 6.8 (0.6)* | 5 (1.5) | 1.5 (0.78) | 3.5 (1.3)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 16 | Kyung Hyun Shin | Korea | 4.96 (2.54) | 3.25 (1.48) | 1.71 (2.2) | 8.74 (1.5) | 2.88 (1.01) | 5.86 (1.32)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 17 | Anqi Wang | China | 7.05 (0.76) | 1.2 (0.62) | 5.85 (0.7)* | 7.15 (0.67) | 1.1 (0.64) | 6.05 (0.66)* | 28.15 (1.69) | 10.65 (0.81) | 17.5 (1.46)* | 113.3 (45.44) | Not reported | ||

| 18 | Stylianos Kapetanakis | Greece | 9.1 (0.79) | 0.76 (0.71) | 8.34 (0.8)* | 6.6 (0.58) | 3.4 (0.86) | 3.2 (0.76)* | Not reported | Not reported | – | 31.6 (8.2) | Not reported | ||

| 19 | Yong Ahn | Korea | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | – | Not reported | Not reported | ||

| 20 | Burcu Goker | Turkey | 4.98 (0.52) | 0.36 (0.18) | 4.62 (0.5)* | 8.58 (0.23) | 0.26 (0.03) | 8.32 (0.2)* | Reported as percentage | Reported as percentage | – | 33.76 (2.64) | Not reported | ||

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation). *, P<0.05 by paired t-test. pre-op, pre-operation; post-op, post-operation; VAS, visual analog scale; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; TF, transforaminal; IL, interlaminar.

Re-recurrence and complications

As per Table 3, all studies reported complications encountered, and the pooled rate across studies were: dural tear (n=10, 0.88%), infection (n=1, 0.09%), transient dysesthesia (n=13, 1.14%), transient headache (n=5, 0.44%), instability (n=8, 0.70%), persistent leg pain (n=7, 0.62%), transient weakness (n=1, 0.09%) permanent neurologic deficit (n=1, 0.09%). 17 studies (85%) reported re-recurrence rates of herniated disc after PELD, with a total of 58 recurrences out of 1,018 discs, or 5.70% pooled recurrence rate.

Table 3

| Study No. | First author | Country/region of origin | Spinal levels operated on | Dural tears | Infection | Epidural hematoma | Nerve root injury | Transient dysesthesia | Transient headache | Instability | Transient weakness | Persistent leg pain | Permanent neuro deficit | PELD re-recurrence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (endoscopic) | Total | L4–5 | L5–S1 | Other | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | Yuan Yao | China | 28 | 28 | 19 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 2 | Yuan Yao | China | 47 | 47 | 20 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 3 | Chao Liu | China | 209 | 209 | 127 | 82 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| 4 | Sebastien Ruetten | Germany | 50 | 50 | 24 | 17 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 5 | Jung-Sup Lee | Korea | 35 | 35 | 27 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 6 | Chi Heon Kim | Korea | 10 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 7—IL | Koichi Yoshikane | Japan | 16 | 17 | 3 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 7—TF | Koichi Yoshikane | Japan | 33 | 35 | 26 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 8 | Gang Xu | China | 31 | 31 | 24 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not reported |

| 9 | YunHee Choi | Korea | 33 | 33 | 18 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Not reported |

| 10 | Thomas Hoogland | Germany | 262 (238 completed 2-year follow-up) | 262 | 137 | 113 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 11 |

| 11 | Shifeng Jiang | China | 24 | 24 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not reported |

| 12 | Chi Heon Kim | Korea | 26 | 26 | 15 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 13 | Dong Yeob Lee | Korea | 25 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 14—IL | Antao Lin | China | 39 | 39 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14—TF | Antao Lin | China | 57 | 57 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | Keng-Chang Liu | Taiwan | 24 | 24 | 8 | 16 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 16 | Kyung Hyun Shin | Korea | 41 | 41 | 26 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 17 | Anqi Wang | China | 24 | 24 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 18 | Stylianos Kapetanakis | Greece | 45 | 45 | 26 | 11 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | Yong Ahn | Korea | 43 | 43 | 35 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | Burcu Goker | Turkey | 60 | 60 | 26 | 28 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Total (N) | 1,162 | 1,165 | 714 | 389 | 62 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 58 | ||

| Rates | 61.3% | 33.4% | 5.32% | 0.88% | 0.09% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.14% | 0.44% | 0.70% | 0.09% | 0.62% | 0.09% | 5.70% | ||||

PELD, percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy.

Meta-analysis: PELD compared to MIS-TLIF

There were 4 studies that compared PELD against MIS-TLIF in management of R-LDH, and the results of the meta-analysis are depicted in Figure 3 while the data extracted from MIS-TLIF arm are depicted in Tables S1-S3. MIS-TLIF had significantly higher reduction in VAS back pain (P<0.001, Figure 3A), significantly higher operation time (P<0.001, Figure 3D), and significantly lower re-recurrence rate (P<0.001, Figure 3E) compared to PELD. MIS-TLIF and PELD had equivalent reduction in VAS leg pain (P=0.39, Figure 3B), improvement in ODI (P=0.55, Figure 3C), and both major (P=0.39, Figure 3G) and total (P=0.32, Figure 3F) complication rates (excluding re-recurrence). Major complications were defined as: dural tear, permanent neurologic deficit, intervertebral infection, instability, adjacent segment disease, or epidural hematoma.

When assessing publication bias, we found that studies comparing PELD to MIS-TLIF were typically distributed around a central line of no effect, signaling no publication bias (29,33,35,36). One outcome, improvement of VAS back scores, had one study with a heavily imprecise estimate. This study, by Liu et al. (2017), had a strong effect favoring MIS-TLIF with an effect size indicating it as an outlier point (29).

Meta-analysis: PELD compared to OLM

There were 2 studies that compared PELD against OLM in management of R-LDH, and the results of the meta-analysis are depicted in Figure 4 while the data extracted from OLM arm are depicted in Tables S4-S6. Of these studies, only one reported data on VAS back and leg, of which PELD arm received greater improvement in VAS back pain and there was no difference in VAS leg pain (Figure 4A,4B). ODI score was not reported in either study. Operation time was also reported by only one study and it was shorter in the PELD arm (Figure 4C). There was no difference in re-recurrence rate (Figure 4D), total (Figure 4E) and major (Figure 4F) complication rates between the two arms. We were able to assess complication rates (major and total), as well as re-recurrence rates, via funnel plots and sensitivity analyses with similar findings of no publication bias. Other outcomes (VAS/NRS and ODI) contained either insufficient observations or inability to converge during Tau2 estimation, signaling a need for more studies to assess for publication bias.

Meta-analysis: PELD compared to MED

There were 2 studies that compared PELD against MED in management of R-LDH, and the results of the meta-analysis are depicted in Figure 5 while the data extracted from MED arm are depicted in Tables S7-S9. There was no significant difference between the two arms in VAS back, leg, ODI, re-recurrence, and complication rates (Figure 5). We were unable to assess for publication bias due to insufficient observations.

Meta-analysis: PELD IL vs. TF approach

Although two studies compared IL and TF approaches of PELD against each other, the pooled analysis across all 20 studies is depicted in Figure 6. There was no significant difference in VAS back, leg improvement, major complications in IL approach, TF approach, or use of both approaches. There was a higher number of total complications in studies utilizing both TL and IF approach compared to studies utilizing only one approach (Figure 6F). ODI was only reported by studies that utilized a TF approach and therefore no comparison was able to be made. We were unable to assess for publication bias due to insufficient observations.

Other study conclusions

The study by Yao et al. (2017) showed that both PELD and MED arms had not measurable blood loss, a shorter hospital stay, and lower cost compared to MIS-TLIF arm (35). The study by Ruetten et al. compared both IL and TF PELD against MED for R-LDH and found equivocal improvements in VAS leg, VAS back, and ODI scores between the two group 2 years after surgery (31). The study by Lee et al. compared PELD against OLM and found equivalent improvement in VAS leg, VAS back, and ODI scores at mean follow up of approximately 2 years, but OLM had significantly higher rates of dural tear (27). The study by Lee et al. found that PELD had significantly shorter operating time and shorter hospital stay than OLM. They also found no difference between groups regarding VAS back, VAS leg, ODI, complication rate and re-recurrence rate (26). The study by Lin et al. compared TF to IL and found IL to have significantly less operative time and intraoperative fluoroscopy time. The two groups had similar blood loss, post-operative VAS back and leg, ODI, Japanese Orthopedic Association, and MacNab Criteria scores (28). Meanwhile, the study by Yoshikane et al. compared TF and IL approaches for R-LDH and found that the two groups had similar operation time and NRS improvement in lower limb, but the IL group had significantly less back pain at follow-up (9). The study by Jiang et al. did not find a difference in VAS and ODI at 1 day, 3 months, and 1 year after surgery between laminectomy group and PELD, as well as no difference in complication rate. They did find PELD to have significantly less bleeding, hospitalization time, operation time, and smaller incision length (22).

Risk of bias

The risk of bias assessment for each study is detailed for cohort studies in Table S10, case-series in Table S11, and RCT in Table S12. Cohort studies were notable for generally very good methodological quality with studies being given “definitely yes” or “probably yes” in most categories. The case-series studies were also of generally very good quality but were limited in that the patients were only recruited from one center for 7 out of 8 studies, and no reporting of loss to follow-up for 7 out of 8 studies. The RCT by Ruetten et al. was of reasonable quality, scoring “some risk of bias” in the overall section (31). It was limited by its use of alternation in selecting study arms for participants instead of a true randomization method such as flipping a coin, and lack of blinding. Additionally, all studies shared a common weakness in not describing the utilization of co-interventions, namely injections or pain medications and conservative treatment such as physical therapy which could have influenced results.

Discussion

Is PELD an effective treatment for R-LDH?

Per Table 2, all studies that reported ODI or VAS/NRS back and leg score included in analysis showed clear improvements in all metrics after the procedure. The studies all had at least 12 months of follow-up, suggesting that the pain relief is long-lasting. Therefore, we can conclude that PELD is in fact an effective tool in the management of R-LDH.

PELD: complications and re-recurrence rates

Our review found that the complication rates for PELD are generally low, with 1 case of permanent neurological deficit to be noted. This reportedly occurred during placement of the working channel. Ankle dorsiflexion strength decreased from Grade 5 to Grade 1 in this patient with no improvement after 52 months of follow-up (29). Although this case should be noted, our data supports that PELD can be seen as a generally safe technique in management of R-LDH.

When examining the literature of management of initial, non-recurrent LDH by PELD, a systematic review by Li et al. found TF endoscopic spine surgery and IL endoscopic spine surgery to have similar effects on VAS back, VAS leg, and ODI scores for patients, with similar rates of recurrence of LDH at 11.6% and 14.3% respectively (31). Our study identified a re-recurrence rate of 5.70% at revision surgery which may be slightly less than or equal to that of the initial recurrence, although duration of follow up was inconsistent amongst included studies, limiting our ability to draw a definitive conclusion.

MIS-TLIF vs. PELD

Our meta-analysis reveals that MIS-TLIF is a compelling alternative to PELD. However, it must be noted that the study by Liu et al. (29) was given the most weight given its large sample size, the VAS back result had a high I2 suggesting a significant heterogeneity amongst studies, only TF PELD approach was utilized in these studies, and for VAS back Liu et al. (29) had a very low pre-operative score of 3.7. This was the lowest pre-operative VAS back score amongst all 19 studies examining PELD, raising the question if these patients were ideal PELD candidates where VAS back pain could even be significantly improved. This study, as noted in the analysis of publication bias, may be subject to a different study design or random error that may skew the overall finding in VAS back to favor MIS-TLIF.

Further, 3 of the 4 studies had 12 months of follow-up while Liu et al. (29) had a mean of nearly 4 years of follow-up. Therefore, Liu et al. (29) was the only study which captured the major complication of adjacent segment disease which often takes several years to develop and is a complication that is theoretically nonexistent amongst PELD patients. Thus, it is quite likely that the major complication rate for the MIS-TLIF arm would be higher in the long term than is reported. In all 4 studies, the major complication rate was higher in the MIS-TLIF arm even though the overall difference was not significant. Major complications are rare events and would require a large sample size to capture a difference but can be devastating and require revision surgery. This should be balanced against the higher rate of re-recurrence seen amongst PELD. Interestingly, ODI was equivalent between the two modalities suggesting that patients achieve equal functional improvement despite the differences identified in our meta-analysis. PELD can still be favored amongst patients who are not candidates for general or spinal anesthesia or otherwise require a shorter operative time. As all 4 studies were cohort studies, our results certainly demonstrate the need for a RCT comparing these surgical techniques, and the utility of IL approach should be explored against MIS-TLIF.

OLM vs. PELD

Our results suggest that PELD could be superior in management of R-LDH compared to OLM. However, we only had one study that showed VAS outcomes where VAS back was improved in the PELD group greater than OLM. While there was no statistical significance in difference in total and major complications, they do approach statistical significance and both outcomes favor PELD with P values of 0.06. The lack of significance is most likely due to lack of studies comparing the two modalities and therefore a lack of power to draw a definitive conclusion. Only one study reported operation times and found PELD to have shorter time than OLM. However, if the operation time and complication rates are truly lower in PELD, and PELD can be performed under sedation while OLM cannot, and if these results are shown in additional studies, this could suggest a new gold standard of management of R-LDH with PELD. An examination of PELD against OLM amongst initial herniated disc found no difference in VAS-back pain or ODI at 24 months, and no significant difference in complication rates and re-recurrences, which is contrary to our findings for R-LDH, and there may possibly be greater advantage for PELD when managing R-LDH as a revision surgery compared to initial herniated disc (37).

MED vs. PELD

Our meta-analysis shows that there were no differences in outcomes between MED and PELD based on two studies. Although not significant, there was a higher rate of total and major complications in the MED groups than the PELD groups (P=0.48, and 0.11 respectively). This portion of the meta-analysis was limited by only having two studies, and given that major complications are rare, devastating events, a large sample size would be required to detect a difference. It is important for future studies to compare these two modalities and determine if the complication rates are truly higher in the MED arm. This could support the use of PELD over MED. Interestingly, a meta-analysis comparing MED against PELD in the management of initial LDH found no difference in VAS leg pain, low back pain, and ODI scores within 2 years post-operation, but PELD achieved better outcomes in back VAS and ODI scores after 2 years post-operatively, suggesting a long follow up time is needed to ascertain differences between these two cohorts. The study also found no difference in complication rate between MED vs. PELD (38).

IL vs. TF PELD

IL and TF PELD achieved similar outcomes in VAS back and leg scores, operation time, re-recurrence rates, and complication rates, but the complication rate was higher in studies that utilized both approaches than studies that utilized a single approach. This finding is difficult to explain as for each individual patient, studies that used both approaches would have only used one approach per patient. Our analysis does not account for the severity of disc herniation and comorbidities as well as other confounders, which may have been disproportionately present in those studies that utilized both approaches and led to the higher rate of complications post-operatively. The results of IL and TF having similar outcomes was shown in a meta-analysis of initial herniated disc, and our results are consistent with this at the stage of R-LDH as well (39).

Limitations

Although some studies compared PELD against open discectomy (n=2), laminectomy (n=1), and MED (n=2), we believe there are too few studies in the literature, and therefore insufficient power, to draw a conclusion regarding which technique is superior to manage R-LDH at this time (22,26,27,31,35). Generally, however, PELD was found to have similar outcomes on ODI and VAS scores with less blood loss, shorter operative times, and quicker recovery time when managing R-LDH. Additionally, we do not believe there is enough data in the literature to support a clearly superior approach (IL vs. TF) for management of R-LDH. Clinical judgement on an individual case will be crucial in making the decision between the two approaches.

Although not captured by risk of bias analysis, it is worth mentioning that only one study, by Xu et al. included information on the type of LDH at time of revision surgery, and it was categorized as: protrusion, subligamentous extrusion, transligamentous extrusion, or sequestration (34). Xu et al. was also the only author to provide information on Modified Pfirrmann Grade of Lumbar Disc Degeneration (34). Amongst our four studies included in meta-analysis, only 3 studies reported the location of disc herniation between the study arms as paramedian or central, the migration status, as well as presence of Modic changes (33,35,36). These warrant subgroup analysis in future studies, as it is possible that each surgical approach has an advantage depending on these characteristics.

No study reported the use of co-interventions such as physical therapy, injections, medications, or other conservative management of R-LDH. Further, the study by Kapetanakis et al. was the only study to report multiple comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, smoking and body mass index), which can affect complication rates and wound healing (23). These areas may also have served as confounders in the cohort and RCT studies, as no study performed multivariate analysis or otherwise adjusted for confounders. Future studies should address the aforementioned issues.

Conclusions

PELD is a safe, effective technique in the treatment of R-LDH based on studies of reasonable quality and methodology. Our meta-analysis reveals TF approach of PELD is equivalent to MIS-TLIF in terms of ability to improve patient’s functional capacity with shorter operative time, and RCTs comparing PELD against MIS-TLIF, MED, and OLM are warranted as there is currently insufficient evidence to state which of these modalities is superior.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://jss.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jss-24-47/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jss.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jss-24-47/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jss.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jss-24-47/coif). S.K. reports that he has been the recipient of Elliquence grant twice to support the endoscopic spine fellowship at his institution. The grant is awarded to the institution to support fellows’ salary and incidentals. He also serves as an expert witness for multiple cases involving complications related to the practice of endoscopic spine surgery. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Peabody T, Black AC, Das JM. Anatomy, Back, Vertebral Canal. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Awadalla AM, Aljulayfi AS, Alrowaili AR, et al. Management of Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023;15:e47908. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gugliotta M, da Costa BR, Dabis E, et al. Surgical versus conservative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012938. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amin RM, Andrade NS, Neuman BJ. Lumbar Disc Herniation. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2017;10:507-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yeung AT, Tsou PM. Posterolateral endoscopic excision for lumbar disc herniation: Surgical technique, outcome, and complications in 307 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:722-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoogland T, Schubert M, Miklitz B, et al. Transforaminal posterolateral endoscopic discectomy with or without the combination of a low-dose chymopapain: a prospective randomized study in 280 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:E890-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pan M, Li Q, Li S, et al. Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy: Indications and Complications. Pain Physician 2020;23:49-56. [PubMed]

- Huang W, Han Z, Liu J, et al. Risk Factors for Recurrent Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2378. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshikane K, Kikuchi K, Izumi T, et al. Full-Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy for Recurrent Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Retrospective Study with Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Spine Surg Relat Res 2021;5:272-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang B, Liu S, Liu J, et al. Transforaminal endoscopic discectomy versus conventional microdiscectomy for lumbar discherniation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2018;13:169. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuan C, Wang J, Zhou Y, et al. Endoscopic lumbar discectomy and minimally invasive lumbar interbody fusion: a contrastive review. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2018;13:429-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni AG, Bassi A, Dhruv A. Microendoscopic lumbar discectomy: Technique and results of 188 cases. Indian J Orthop 2014;48:81-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mooney J, Erickson N, Salehani A, et al. Microendoscopic lumbar discectomy with general versus local anesthesia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. N Am Spine Soc J 2022;10:100129. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cochrane. Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Cohort Studies. Available online: https://www.distillersr.com/resources/methodological-resources/tool-to-assess-risk-of-bias-in-cohort-studies-distillersr

- Economics IoH. Development of a quality appraisal tool for case series studies using a modified Delphi Technique. 2012. Available online: https://cobe.paginas.ufsc.br/files/2014/10/MOGA.Case-series.pdf

- Cochrane. RoB 2: A revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials 2019. Available online: https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2021.

- Ahn Y, Lee SH, Park WM, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy for recurrent disc herniation: surgical technique, outcome, and prognostic factors of 43 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:E326-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi Y, Kim CH, Rhee JM, et al. Longitudinal clinical outcomes after full-endoscopic lumbar discectomy for recurrent disc herniation after open discectomy. J Clin Neurosci 2020;72:124-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goker B, Aydin S. Endoscopic Surgery for Recurrent Disc Herniation After Microscopic or Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy. Turk Neurosurg 2020;30:112-8. [PubMed]

- Hoogland T, van den Brekel-Dijkstra K, Schubert M, et al. Endoscopic transforaminal discectomy for recurrent lumbar disc herniation: a prospective, cohort evaluation of 262 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:973-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiang S, Li Q, Wang H. Comparison of the clinical efficacy of percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy and traditional laminectomy in the treatment of recurrent lumbar disc herniation. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e25806. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kapetanakis S, Gkantsinikoudis N, Charitoudis G. The Role of Full-Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy in Surgical Treatment of Recurrent Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Health-Related Quality of Life Approach. Neurospine 2019;16:96-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim CH, Chung CK, Jahng TA, et al. Surgical outcome of percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar lumbar diskectomy for recurrent disk herniation after open diskectomy. J Spinal Disord Tech 2012;25:E125-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim CH, Chung CK, Sohn S, et al. The surgical outcome and the surgical strategy of percutaneous endoscopic discectomy for recurrent disk herniation. J Spinal Disord Tech 2014;27:415-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee DY, Shim CS, Ahn Y, et al. Comparison of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy and open lumbar microdiscectomy for recurrent disc herniation. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2009;46:515-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JS, Kim HS, Pee YH, et al. Comparison of Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Diskectomy and Open Lumbar Microdiskectomy for Recurrent Lumbar Disk Herniation. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg 2018;79:447-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin A, Wang Y, Zhang H, et al. Endoscopic Revision Strategies and Outcomes for Recurrent L4/5 Disc Herniation After Percutaneous Endoscopic Transforaminal Discectomy. J Pain Res 2024;17:761-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu C, Zhou Y. Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Diskectomy and Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion for Recurrent Lumbar Disk Herniation. World Neurosurg 2017;98:14-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu KC, Hsieh MH, Yang CC, et al. Full endoscopic interlaminar discectomy (FEID) for recurrent lumbar disc herniation: surgical technique, clinical outcome, and prognostic factors. J Spine Surg 2020;6:483-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruetten S, Komp M, Merk H, et al. Recurrent lumbar disc herniation after conventional discectomy: a prospective, randomized study comparing full-endoscopic interlaminar and transforaminal versus microsurgical revision. J Spinal Disord Tech 2009;22:122-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shin KH, Chang HG, Rhee NK, et al. Revisional percutaneous full endoscopic disc surgery for recurrent herniation of previous open lumbar discectomy. Asian Spine J 2011;5:1-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang A, Yu Z. Comparison of Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy with Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion as a Revision Surgery for Recurrent Lumbar Disc Herniation after Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2020;16:1185-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu G, Zhang X, Zhu M, et al. Clinical efficacy of transforaminal endoscopic discectomy in the treatment of recurrent lumbar disc herniation: a single-center retrospective analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023;24:24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yao Y, Zhang H, Wu J, et al. Comparison of Three Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery Methods for Revision Surgery for Recurrent Herniation After Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy. World Neurosurg 2017;100:641-647.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yao Y, Zhang H, Wu J, et al. Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Versus Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy: Revision Surgery for Recurrent Herniation After Microendoscopic Discectomy. World Neurosurg 2017;99:89-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jarebi M, Awaf A, Lefranc M, et al. A matched comparison of outcomes between percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy and open lumbar microdiscectomy for the treatment of lumbar disc herniation: a 2-year retrospective cohort study. Spine J 2021;21:114-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu J, Li Y, Wang B, et al. Minimum 2-Year Efficacy of Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy versus Microendoscopic Discectomy: A Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg 2020;138:19-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li WS, Yan Q. Global Spine J 2022;12:1012-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]