The modern application of anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF): a narrative review of perioperative considerations and surgical pearls

Introduction

Lumbar interbody fusion (LIF) is a well-established treatment for spinal disorders, including degenerative pathologies, deformity, trauma, infection, and neoplasia (1). Common indications for LIF include discogenic back pain, neurogenic claudication, radiculopathy, symptomatic spondylolisthesis, and scoliosis (2). LIF uses a structural interbody graft, such as an allograft or metallic cage, inserted into the intervertebral disc space to stabilize motion, restore disc height, and promote bony arthrodesis (2). It is often performed alongside surgical decompression techniques like discectomy and bony resection.

Anterior and lateral approaches have gained attention for their smaller incisions, reduced postoperative pain, and shorter recovery times. The anterior LIF (ALIF) is commonly used to access the L5/S1 and L4/L5 disc spaces without entering the spinal canal or neural foramina. Surgeons can achieve indirect decompression with ALIF, often avoiding the need for posterior decompression, which in deformity or severe degenerative cases carries risks of iatrogenic damage to the dura mater and nerve roots (3). The technique also allows greater disc resection and easier endplate preparation (2,4,5). Additionally, ALIF preserves the paraspinal muscles and posterior ligamentous structures critical for spinal stability (6). While ALIF is a valuable tool for spinal surgery, it requires a skilled approach due to its proximity to critical neurovascular and soft tissue structures. Thus, thorough understanding and execution are essential for safe surgery. This review discusses the modern application of ALIF with a specific emphasis on perioperative and intraoperative management as well as surgical pearls that can be practically implemented by spine surgeons. We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://jss.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jss-24-85/rc).

Methods

The search strategy involved a comprehensive review of literature from three primary databases: PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library. The search terms included both MeSH terms and free text words such as “anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF)”, “lumbar spine surgery”, “spinal fusion outcomes”, “perioperative considerations”, and “surgical techniques”. The timeframe for the search was set from 1990 to 2024.

Inclusion criteria comprised peer-reviewed articles, studies in English, case reports/series, and those involving human subjects. Non-English articles were excluded from the review. The selection process was carried out independently by two reviewers to ensure objectivity and thoroughness. Any discrepancies in the selection process were resolved through discussion and reaching a consensus (Table 1).

Table 1

| Items | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Date of search | December 1, 2023–April 1, 2024 |

| Databases and other sources searched | PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library |

| Search terms used | Anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF), lumbar spine surgery, spinal fusion outcomes, perioperative considerations, surgical techniques |

| Timeframe | 1990–2024 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion: peer-reviewed articles, studies in English, human subjects, case reports/series |

| Exclusion: non-English articles | |

| Selection process | Selection was conducted independently by two reviewers, discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus |

This structured approach ensured a comprehensive and balanced review of the current literature on the modern application of ALIF, focusing on perioperative considerations and surgical pearls.

Development of ALIF

In 1935, Capener first described the anterior method for inserting a bone graft spacer to treat spondylolisthesis (7), though some argued it caused excessive surgical trauma (8). Surgeons like Phan and Mercer later reported successful corrections using this technique (9,10). Stabilization of the spinal segment prevented further slippage, resulting in pain relief and improved function, with radiographic evidence of fusion. Iwahara introduced a retroperitoneal method in 1944 (11), and by 1948, Lane and Moore reported a 94% clinical success rate in treating lumbar disc disease using ALIF, despite a fusion rate of only 54% with allogenic bone grafts (12). Hodgson and Stock applied this approach to treat Pott’s disease, which laid the foundation for modern ALIF surgery involving necrotic tissue debridement, spinal decompression, and insertion of corticocancellous bone blocks (13,14). Cloward used similar methods with cylindrical dowels, influencing later surgeons like Harmon and Sacks, who favored anterior fusion (15-17). O’Brien et al. proposed using trapezoid blocks, which evolved into a hybrid strategy with biologic cages made from femoral cortical allografts filled with cancellous bone (18).

In the 1970s and 1980s, the use of stand-alone ALIF increased, with varied surgical approaches and differing fusion success rates. ALIF with posterior fusion as a supplementary technique gained popularity. However, there is still debate about the superiority of posterior supplemented ALIF vs. stand-alone ALIF for lumbar degenerative spine disease (10). Advancements in ALIF technology, including the development of implant cages and devices to restore disc height and enhance stability, have continued. Anterior spinal instrumentation has improved mechanical stability and fusion rates (19). Interbody cages have evolved in material, shape, and size, with newer devices featuring porous structures to promote fusion (20). Some interbody devices used in anterior approaches may include plate fixation or integrated screws, improving stabilization without repositioning or posterolateral fusion. Biomechanical data indicates improved structural rigidity with the addition of pedicle screw fixation (10).

Indications and contraindications

Indications

ALIF is indicated for various conditions, emphasizing careful patient selection after exhausting conservative treatments. Patients with refractory low back pain, with or without radicular pain, may benefit from ALIF depending on the underlying pathology. ALIF is particularly effective in treating spondylolisthesis, including isthmic and degenerative types (21). For isthmic subluxation, where there is a pars interarticularis defect, ALIF reduces the slipped vertebra and promotes stability with incorporated screws, forming a fused segment. In degenerative spondylolisthesis, ALIF has higher fusion rates, superior outcomes, and fewer neurological deficits compared to posterior decompression for grade I and II cases (22).

ALIF is also indicated for disc pathology such as degenerative disc disease (DDD) and discitis. It alleviates DDD symptoms by removing the degenerated disc, restoring disc height, and improving biomechanical stability (23,24). Since disc height loss reduces neuroforamen size, ALIF helps decompress the nerve root by enlarging the foramen, addressing radiculopathy (25). Disc pathology can also cause vertebral translation and posterior disc bulging. These factors contribute to central spinal stenosis and neurogenic claudication, and ALIF can decompress the canal by removing degenerative material, restoring disc height, and stabilizing the segment (26). Indirect decompression via ALIF is often sufficient for symptom relief, potentially eliminating the need for posterior decompression (27). However, careful preoperative and intraoperative assessment is required for each case (22).

Pseudoarthrosis, or failed spinal fusion, is another indication for ALIF. ALIF improves the fusion environment and corrects previous fusion failures. It is often used to augment posterior fusion to achieve circumferential fusion, offering excellent disc space access and thorough endplate preparation with larger grafts (28). ALIF is also beneficial for adjacent segment disease, reducing motion and providing additional fusion in revision surgeries.

ALIF is a valuable tool in deformity correction, particularly for pelvic incidence-lumbar lordosis (PI-LL) mismatch and sagittal deformity correction (29). The lower lumbar segments contribute most of the lumbar lordosis, and ALIF’s access to the L4–L5 and L5–S1 spaces, combined with the ability to remove anterior osteophytes and the ossified anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL), make it effective for restoring lumbar alignment. In degenerative scoliosis, ALIF helps correct coronal malalignment by releasing contracted tissues, removing osteophytes, and distracting the intervertebral space (30). Other ALIF indications include Pott’s disease, recurrent lumbar disc herniation, post-discectomy collapse, dislocation, and trauma-induced disc rupture (21), highlighting the versatility of ALIF across spinal pathologies.

Contraindications

Contraindications to ALIF include conditions and comorbidities that significantly increase the risk of complications. These include active infection at the surgical site, severe cardiovascular disease, and unstable medical conditions like poorly controlled diabetes or coagulation disorders. Allergic reactions to metals or bone graft materials are also absolute contraindications. Pregnancy, severe obesity, and severe vascular disease are additional factors that discourage ALIF (31). Aorto-iliac aneurysms are a strong vascular contraindication due to the complexity of artery displacement. Anatomical variations, whether vascular or urologic, may complicate the spinal approach, underscoring the importance of preoperative imaging.

Relative contraindications indicate increased risk but do not fully exclude the procedure. Organ defects and extreme obesity fall into this category, as the prone position for ALIF may be less tolerated by patients with respiratory insufficiency. Caution is advised in patients with a history of phlebitis or pulmonary embolism, particularly with anterior approaches to L4/L5 requiring venous mobilization (32). A history of radiation therapy, especially involving the aorto-iliac lymph node chains, is another relative contraindication. Direct posterior decompression may be needed in some cases, though an anterior fusion-reduction stage can still be performed (3). While most disc herniations can be treated with an anterior approach, extruded hernias may still require posterior intervention (3).

Preoperative evaluation

A thorough preoperative evaluation, including a detailed patient history, physical exam, and review of radiographic and advanced imaging studies, is crucial in properly selecting patients for ALIF surgery. A comprehensive medical history must identify factors that could impact the procedure, such as prior abdominal or spine surgery, infection, or clotting disorders. Understanding the patient’s back and lower extremity symptoms is key. This includes distinguishing between mechanical axial pain, radicular pain, and claudicatory pain, which is important for diagnosing the underlying spine pathology. Mechanical pain often originates from structural issues in the spine, such as degenerative changes or instability. In contrast, radicular pain, associated with nerve root compression, radiates along a specific nerve dermatome and may involve numbness, tingling, or weakness. Neurogenic claudication typically presents as posterior thigh pain, weakness, or numbness during walking or standing, often due to central spinal stenosis.

Careful history-taking, combined with a physical exam and imaging review, helps differentiate these pain types and guide treatment options, improving the success of ALIF. It also helps determine the need for concomitant procedures. The patient’s posture is assessed to detect deformities such as scoliosis, kyphosis, or sagittal imbalance. Prior abdominal surgeries or spine procedures should be noted. Gait observation helps identify compensatory movements or neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s. Identifying conditions such as hip or knee arthritis is also important, as these may confound the pain distribution. The exam continues with palpation of the spine to check for tenderness or deformities, and of the abdomen to check for hernias or prior mesh placements relevant to surgical planning. The exam concludes with an assessment of the pelvis and hips.

A thorough neurologic examination is essential in the preoperative assessment, focusing on the lumbar spine and lower extremities. This includes motor grading to identify weakness from nerve root compression, sensory evaluation of dermatomes using light touch and pinprick, and reflex testing (e.g., patellar and Achilles reflexes) to assess nerve root function. Tests like the Straight Leg Raise help identify sciatic nerve irritation and lumbar nerve involvement.

Careful consideration of vascular factors is essential to minimize complications and ensure patient safety. Screening for an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is critical, as an AAA may require changes to the surgical plan (33). The evaluation should also include lower limb perfusion, review of conditions such as peripheral artery disease (PAD), and a thorough examination of peripheral pulses and signs of compromised blood flow. Dislodging calcifications within the great vessels during surgery can lead to distal embolic events and limb ischemia. It is important to differentiate symptoms of vascular claudication from neurogenic claudication preoperatively.

Imaging

X-ray

Preoperative imaging plays a pivotal role in the planning and execution of ALIF, employing X-rays to offer a comprehensive assessment of the lumbar spine. The primary purpose is to gain insights into both coronal and sagittal spinal alignment and stability while evaluating for degenerative changes, disc height loss, deformities, or fractures. Various types of X-rays are recommended during preop evaluation; these include anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral views, flexion, and extension views of the lumbar spine, and full-length scoliosis films (Figure 1A-1D). It also allows for assessment of spino-pelvic parameters which can assist in setting appropriate correction targets with ALIF and other concomitant procedures. Crucially, the imaging aids in identifying signs of instability such as spondylolisthesis (Figure 2). Additionally, these X-rays serve the purpose of locating and assessing hardware from previous surgeries.

CT scan

CT scans serve a pivotal role in providing a comprehensive assessment of the lumbar spine’s bony structures and facet joints. This imaging modality plays a crucial role in evaluating the degree of disc degeneration, identifying spinal stenosis, and can serve as a useful tool when assessing the bony patency (or lack thereof) of neural foramina (Figure 3A). The presence and extent of disc degeneration can be scrutinized, such as identifying vacuum disc phenomenon (Figure 3A), which aids in localization of pathological changes that may be significant pain generators. Furthermore, the CT scan allows for the identification of additional bony abnormalities, including osteophytes or fractures, which are vital considerations in the preoperative planning process (Figure 3A,3B). CT can also be useful in identifying transitional lumbar-sacral anatomy which may play a role in discerning which spine segments to operate on and the feasibility of accessing such anatomy if it is present. Moreover, CT can be used to assess bone quality of the host (i.e., Hounsfield unit) (34).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI plays a pivotal role in providing detailed visualization of soft tissues, specifically intervertebral discs, nerves, and surrounding crucial structures. The examination focuses on disc morphology, evaluating the hydration status, and identifying signs of degeneration. Moreover, MRI allows for the precise assessment of spinal cord and nerve root compression, providing crucial information about the extent and location of neural impingement (Figure 4). The identification of foraminal or central stenosis is another key aspect of the imaging process, aiding in understanding potential sources of nerve compression which can include herniated disc material, facet arthropathy, and hypertrophied ligamentum flavum. Delineating the anatomic contributions to the neurocompression at a given level and their potential correlated physical exam findings is crucial for gauging the degree of which decompression can be achieved from anterior surgery. For example, if the symptomatic neurocompression is driven mostly by degenerative disc material extending posterior into the canal and/or foramen, as seen on MRI, then indirect decompression via the ALIF may suffice. However, if there is significant lateral recess stenosis from a hypertrophied facet joint, that may suggest that additional posterior decompression may be needed for adequate results of the entire procedure.

Furthermore, MRI is instrumental in assessing the vascular anatomy and other soft tissue structures that may pose challenges during the surgical procedure. The aorta and the inferior vena cava (IVC) have their bifurcations into the internal iliac arteries and vessels, respectively, typically at the L4 level (35). MRI plays a significant role in understanding the surgical trajectory and the direction of great vessel retraction on surgical exposure needed to safely access the disc space. In some cases, MRI will demonstrate there is no safe plane to access the disc without significant risk to the vessels, notably, in regard to the internal iliac veins which are easily damageable on account of their friable surrounding membrane. Proper assessment of these factors preoperatively can provide the opportunity to use different strategies to address such spine segment pathology and conduct the procedure safely (Figure 5A-5D).

Additionally, MRI, can serve as a valuable tool for identifying additional spinal levels that may require attention, contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s lumbar anatomy (i.e., confirmation of transitional anatomy), and identify anomalous soft tissue structures (i.e., horseshoe kidney).

ALIF outcomes comparison

ALIF has been compared to other lumbar fusion techniques such as transforaminal LIF (TLIF), extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF), posterior LIF (PLIF), and the oblique Antepsoas approach. Below is a brief comparison of ALIF outcomes with these techniques.

ALIF, PLIF, and TLIF exhibit similar fusion rates, as fusion outcomes depend on factors like patient selection, endplate preparation, and the chosen graft material (36-38). The biomechanical advantages of placing the graft in the load-bearing column of the spine lead to superior fusion rates and improved outcomes compared to posterior fusion techniques (39).

ALIF is more effective at restoring disc height and segmental lordosis than TLIF and XLIF (36). ALIF provides efficient access to the anterior column, enabling thorough clearance of the disc space and placement of a larger interbody device. This contributes to improved disc height and lordosis. This restoration not only facilitates neuroforaminal decompression, relieving radicular symptoms, but also stabilizes the segment, reducing pain associated with abnormal mechanical loading (21,40).

TLIF demonstrates superior Oswestry disability index (ODI) scores compared to ALIF and PLIF (36). This may be due to TLIF’s minimally invasive nature, which results in less iatrogenic injury and surgical trauma, leading to lower ODI scores. However, visual analogue scale (VAS) scores for back and leg pain are comparable across all approaches (36), highlighting the shared goal of neural decompression and segmental stabilization.

Regarding blood loss, PLIF is associated with the highest blood loss, followed by TLIF and ALIF (36). The anterior approach used in ALIF typically results in significantly lower blood loss, assuming no intraoperative vessel injury. The average blood loss for single-level ALIF ranges from 200 to 300 mL, but can rise to 700 mL or more if a tear occurs in the common iliac vein, especially if vascular repair is complex or prolonged (40).

PLIF has higher complication rates than TLIF (36). However, comparisons between ALIF vs. PLIF and ALIF vs. TLIF show no significant differences in complication rates (36), possibly due to variability in the ALIF vs. PLIF comparisons.

ALIF has a higher rate of cage migration (36). This is due to the removal of stabilizing structures like the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments (ALL and PLL) during anterior surgery, which increases the likelihood of postoperative cage migration.

TLIF has a higher rate of subsidence compared to ALIF and PLIF. One study found that TLIF used a single Capstone cage, while ALIF used one Synfix cage, and PLIF used two PEEK cages (41). PLIF had the lowest subsidence rate, likely due to the bilateral placement of two cages, which increased the fusion area and maintained axial load balance (41). In terms of lordosis correction, ALIF produces a greater increase in postoperative segmental lordosis compared to PLIF and TLIF (42). Additionally, ALIF better prevents adjacent segmental disease (43) because it preserves the posterior elements like muscles, ligaments, and facets, which are compromised during PLIF (44).

Kim et al. compared ALIF and PLIF for reducing vertebral body slippage in low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. Both approaches were effective (45). TLIF, however, is less effective at reducing vertebral body slippage, likely due to the unilateral total facetectomy and fixation used (41). ALIF and PLIF allow for a larger interbody surface area, and when combined with posterior bilateral facetectomy and bilateral fixation, offer more durable stability and better reduction of slippage.

In comparing ALIF with the oblique Antepsoas approach [oblique LIF (OLIF)], both techniques showcase similar results in terms of disc height, segmental lordosis, VAS and ODI scores, achieving fusion rates exceeding 90% in both groups (46). Nevertheless, OLIF presents a higher incidence of complications, primarily associated with cage subsidence (46).

According to the most current and reliable evidence available, XLIF surgery carries a significantly higher risk, nearly double, of potential neurological complications (particularly thigh symptoms), which may be transient but could also have lasting effects (47,48). The most significant risk of sensory nerve injury is specifically associated with the manipulation of the psoas muscle and has been acknowledged in previous studies (49-52). This risk persists even when neuromonitoring is employed.

Despite the elevated risk of neurological complications, XLIF demonstrates lower overall complication rates, primarily due to its less invasive nature (47). This includes both the anterior or lateral approach and the less invasive supplemental posterior instrumentation and decompression techniques. And while the use of neuromonitoring and other precautionary measures is recommended to mitigate the risk of neurological complications in XLIF procedures, these measures have not proven effective in reducing the incidence of such complications (47).

Surgical pearls and pitfalls

In this section, we describe a brief overview of ALIF surgical pearls and pitfalls. The techniques described below reflect the practice of the senior author (attending spine surgeon) at a high-volume tertiary center for complex spine surgeries.

Patient positioning

The patient is positioned supine on a radiolucent table. A roll can be placed under the small of the patient’s back when attempting to access the L5–S1 vertebral level which can help extend the pelvis. This can aid in accessing to the lower lumbar segments and maneuvering above the pubis, especially in patients with a high sacral slope and/or with significant spondylolisthesis. The arms are usually abducted from the body to allow space for the surgeon and intraoperative fluoroscopy or more advanced imaging tool (i.e., O-arm) to evaluate implant placement.

Neuro-monitoring

Neuro-monitoring is recommended in most cases as this can help guide safe surgical execution of the various stages of ALIF and the often concomitant posterior spine surgeries. These include somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs), motor evoked potentials (MEPs), and electromyography (EMG) of the nerves at and below the spine segment being operated on. Close monitoring of these neurologic parameters can help surgeons avoid permanent neurologic damage to the structures within close proximity of the surgical instruments and implants. Additionally, they can help prevent neurologic damage by providing intra-operative evidence that an interbody implant may be too large or create too great a degree of lordosis. The former concern may lead to neuropraxic injury of the potentially stretched nerve due to overstuffing or direct nerve contact by the interbody implant. The latter concern of hyperlordosis created by the interbody can in some cases collapse neuroforamen by hinging open the anterior column and collapsing the posterior structures to a point where it compresses the exiting nerve root leading to radiculopathy.

Vascular monitoring

Given that the anterior approach to the spine requires mobilization and retraction of the great vessels, vascular monitoring is advisable. During the initial exposure, a large portion of the disc preparation and instrumentation, the aorta, IVC, and left iliac artery (LIA) and veins are often retracted to the right aspect of the spine to allow for adequate exposure of the disc space. The LIA in particular commonly experiences significant stretch during the case. Therefore, pulse oximetry attached the toe of the left foot should be performed as this provides continual information about the perfusion of the lower extremity. Changes in the oxygen saturations or waveform may indicate the vessels are being stretched to a degree that is affecting the perfusion of the limb in which case the retractors or other surgical maneuvers can be adjusted. Additionally, aortic and iliac vessels calcifications are common in the population of ALIF patients. Significant and persistent reductions of pulse oximetry signals of the lower extremity that do not improve with retractor adjustment should raise the suspicion of thrombo-embolic event and/or serious vascular injury. Immediate consultation with vascular surgery or interventionalists may be required in such cases.

Disc space preparation and instrumentation

Once the anterior disc is exposed by way of the access surgeon, care must be taken to not damage the surrounding structures when entering the disc space. This can be achieved with long-handled knife or electrocautery to incise the perimeter of disc space. This allows the use of a long Cobb elevator to be placed into the disc space directly adjacent to the endplate. With careful rotations of the cobb, the disc material is gently elevated on the endplate (Figure 6A). After sufficient mobilization of the disc material, it can be extracted using rongeurs (Figure 6B). Removal of the cartilaginous end plates is carried out using a series of curettes, rasps, and rongeurs, progressing centrally to laterally to facilitate disc space expansion and eliminate material that could hinder fusion, especially at the lateral aspects of the disc space. The vertebral body end plate is prepared by roughening with grasps and curettes. However, this requires a balance of adequate endplate preparation to solid bleeding endplate bone without carving too deeply and risking implant subsidence.

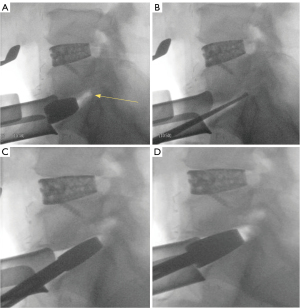

Next, interbody trial implants are inserted on a handle into the disc space and malleted posteriorly. This is performed with increasing larger implants and allows for dilation of the disc space, restoration of intervertebral height, and lordosis (Figure 7A). Intraoperative fluoroscopy in the lateral view is used to assess the size of the trial implant in comparison to the vertebral body endplate dimensions. The surgeon should assess the AP size of the implant and ensure the implants are not jutting too far anterior to the anterior cortex of the body as well as not extending too far posterior into the spinal canal. The assessment of coronal placement of the trials is performed on direct visualization. Further assessment of the degree of lordosis desired can also be done on lateral fluoroscopy. Generally, the surgeon can visualize increased neural foraminal space as larger trials are introduced, indicative of up-down indirect decompression (Figure 7B-7D). Conversely, the surgeon should take note when a trial implant anteriorly hinges open the disc space to a degree where it shrinks the neuroforaminal space posteriorly. This suggests that the lordosis of the trial needs to be balanced with a taller size and should be considered especially when placing hyper-lordotic interbodies.

The surgeon should be cautious to match the trajectory and angle of the disc space when preparing the endplate and inserting trials. Failure to do so may create a shelf within the endplate that blocks the proper insertion of the trials and can lead to suboptimal sizing of final implants. It may also lead to improper position of the interbody that can risk extrusion or subsidence. Lateral fluoroscopic views obtained during this stage are critical for identifying mismatched trajectory and making appropriate corrections (Figure 8A-8D).

Once proper implant trialing is complete and final implant sizing chosen, the final interbody implants must be carefully placed into the prepared disc space. Depending on the interbody material [allograft, polyetheretherketone (PEEK), metallic cage], the central cavitations of the interbody are filled with osteoconductive material to promote fusion (Figure 9A). Care should be taken to place the implant centrally on the endplate in the coronal and sagittal planes. AP and lateral fluoroscopy are obtained to confirm proper implant position prior to inserting any screw fixation. Adjustments of the interbody can be made with gentle malleting of a bone tamp (Figure 9B). Following this, the graft is placed into the disc space and securely anchored with two screws—one caudal and one rostral, driven through the adjacent vertebral bodies. Final lateral and AP fluoroscopic views should be obtained, including a Rosenberg view, to confirm proper implant and screw placement (Figure 10A,10B).

Surgical complications

Like any spinal procedure, ALIF has several potential complications that require careful consideration during surgery and in the postoperative period.

Subsidence, or the collapse of the interbody implant into the vertebral endplates, is a potential complication (53,54). Though rare, subsidence can cause disc height to fall below preoperative levels (55,56). This can lead to severe pain, disc collapse, neural compression, kyphosis, instability, and vertebral fractures (31,57,58). However, a study by Rao et al. found that subsidence did not significantly affect bony fusion, pain, or disability (53). Metal cages are often preferred for maintaining disc space height (54-56).

Visceral injuries, such as ureteral, bowel, or peritoneal injuries, can occur from mobilizing the peritoneum or psoas muscle. Ureteral injuries are rare during primary retroperitoneal exposure but may present with infection signs when they occur (58-63). The risk of ureteral injury is higher in revision surgeries, particularly when removing anterior instrumentation. Bowel and peritoneal injuries are more common in patients undergoing revision surgery or those with prior abdominal surgery, radiation, or malignancy (64). Repair of peritoneal perforations should be immediate. Direct bowel injuries during retroperitoneal exposure range from 2.29% to 16% (65-67). Postoperative ileus occurs in 0.6% to 5.6% of anterior lumbar procedures and is more common with the transperitoneal approach (68).

Vascular complications during ALIF pose risks to major blood vessels, particularly the aorto-iliac region, requiring thorough preoperative imaging and careful intraoperative measures. Vascular injuries occur in 1–15% of cases, with veins (3–4%) more commonly affected than arteries (0.45–1.5%) (64,69-72). The left iliac vein, ascending iliolumbar vein, and IVC are frequently injured, especially at the L4–L5 level, often resulting in thrombosis. Arterial injuries, less common due to the elasticity of the aorta and iliac artery, typically involve the LIA (<0.9% incidence) (70,71) and can cause thrombosis or delayed hemorrhage. Postoperative complications include venous thromboembolism (1–1.6%), arterial thrombosis (0.45–1.3%), and retroperitoneal hematomas (0.49%) (71,73-76). Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) occurs in 7.5% of patients, though routine exams are not recommended (77). Symptoms of iliac vein DVT include leg pain and claudication, with rare progression to pulmonary embolism (0.1%) (70). Arterial thromboembolic events in the left common iliac artery are rare (78).

Pseudoarthrosis, or failure of bone fusion at the graft site, is a major complication in ALIF, often occurring within 3 months postoperatively due to inadequate disc distraction, poor endplate preparation, or undersized cages (64). Proper preoperative planning and surgeon expertise are crucial in evaluating cage tightness. Complication rates vary, with studies reporting rates from 1.97% to less than 1% (70,79). The L5–S1 segment is particularly prone to complications due to poor sacral bone quality, complex sacral anatomy, and high sacral slope (80). Stand-alone ALIF achieves an 88.6% fusion rate, increasing to 94.2% with anterior fixation plates (81). Combining sacropelvic fixation with anterior column support minimizes fusion failure risk, with factors like smoking, graft type, obesity, and prior abdominal surgery influencing outcomes (80,81).

Sympathetic nerve injury is a concern due to the proximity of ganglia to the surgical field, with complications varying based on which nerves are affected. The superior hypogastric plexus is at risk during surgery, particularly with the transperitoneal approach, increasing the chance of retrograde ejaculation and necessitating patient counseling, especially for younger patients (82). Careful handling of vessels and avoiding accidental ligation are crucial surgical considerations (64). Injuries to the lumbar sympathetic trunk from the anterior approach may cause benign temperature changes in the contralateral foot, with sympathetic dysfunction reported in 6.06% of patients (83).

The lumbar and sacral nerve roots may be affected by ALIF, leading to motor and sensory deficits such as weakness, sensory loss, or neuropathic pain (84,85). Nerve root injuries occur due to direct trauma during discectomy or graft placement, or indirect trauma from prolonged retraction or instrument use. Nerve root stretching and ischemia also contribute to postoperative neural deficits (86). Clinical signs include radiculopathy, foot drop, quadriceps weakness, and sensory disturbances (87). The L4–L5 and L5–S1 levels are particularly vulnerable. Minimizing retraction time and using nerve monitoring can reduce risks. Early recognition and treatment, including medication, physical therapy, and surgery if needed, are critical.

Conclusions

The anterior approach is a well-described and validated technique for lumbar fusion. As with any procedure, it is important to thoroughly evaluate patients preoperatively to determine which approach is most reasonable for that individual, along with weighing risks vs. benefits of potential morbidity. When indicated properly and performed safely, ALIF is powerful in addressing many lumbar spinal pathology and should be considered along with other appropriate concomitant procedures. Understanding the anatomical constraints, the intraoperative pitfalls, and the techniques to monitor for and prevent complications further improve the surgeon’s ability to perform successful ALIF procedures. Future studies should aim to evaluate ALIF patients long-term in order to improve technique and surgical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://jss.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jss-24-85/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jss.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jss-24-85/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jss.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jss-24-85/coif). L.M. receives royalties and consulting fees from Alphatec, Evolution Spine, and Medacta. L.M. holds stocks of Alphatec and Zimvie (common stock). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Resnick DK, Choudhri TF, Dailey AT, et al. Guidelines for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. Part 7: intractable low-back pain without stenosis or spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Spine 2005;2:670-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mobbs RJ, Phan K, Malham G, et al. Lumbar interbody fusion: techniques, indications and comparison of interbody fusion options including PLIF, TLIF, MI-TLIF, OLIF/ATP, LLIF and ALIF. J Spine Surg 2015;1:2-18. [PubMed]

- Allain J, Dufour T. Anterior lumbar fusion techniques: ALIF, OLIF, DLIF, LLIF, IXLIF. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2020;106:S149-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kapustka B, Kiwic G, Chodakowski P, et al. Anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF): biometrical results and own experiences. Neurosurg Rev 2020;43:687-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zdeblick TA, David SM. A prospective comparison of surgical approach for anterior L4-L5 fusion: laparoscopic versus mini anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2682-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reisener MJ, Pumberger M, Shue J, et al. Trends in lumbar spinal fusion-a literature review. J Spine Surg 2020;6:752-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Capener N. Skiagrams of a Very Early Case of Spondylolisthesis. Proc R Soc Med 1935;28:1369-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stauffer RN, Coventry MB. Anterior interbody lumbar spine fusion. Analysis of Mayo Clinic series. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1972;54:756-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phan K, Mobbs RJ. Evolution of Design of Interbody Cages for Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Orthop Surg 2016;8:270-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mercer W. Treatment of Spondylolisthesis. Br Med J 1936;2:945. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iwahara T. A new method of vertebral body fusion. Surgery 1944;8:271-87.

- Lane JD Jr, Moore ES Jr. Transperitoneal Approach to the Intervertebral Disc in the Lumbar Area. Ann Surg 1948;127:537-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hodgson AR, Stock FE, Fang HS, et al. Anterior spinal fusion. The operative approach and pathological findings in 412 patients with Pott's disease of the spine. Br J Surg 1960;48:172-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hodgson AR, Stock FE. Anterior spine fusion for the treatment of tuberculosis of the spine: the operative findings and results of treatment in the first one hundred case. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1960;42:295-310. [Crossref]

- Cloward RB. Lesions of the intervertebral disks and their treatment by interbody fusion methods. The painful disk. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1963;51-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harmon PH. Anterior excision and vertebral body fusion operation for intervertebral disk syndromes of the lower lumbar spine: three-to five-year results in 244 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1963;107-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sacks S. Anterior interbody fusion of the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1965;47:211-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Brien JP, Dawson MH, Heard CW, et al. Simultaneous combined anterior and posterior fusion. A surgical solution for failed spinal surgery with a brief review of the first 150 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;191-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel DV, Yoo JS, Karmarkar SS, et al. Interbody options in lumbar fusion. J Spine Surg 2019;5:S19-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jain S, Eltorai AE, Ruttiman R, et al. Advances in Spinal Interbody Cages. Orthop Surg 2016;8:278-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mobbs RJ, Loganathan A, Yeung V, et al. Indications for anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Orthop Surg 2013;5:153-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takahashi K, Kitahara H, Yamagata M, et al. Long-term results of anterior interbody fusion for treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1990;15:1211-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pradhan BB, Nassar JA, Delamarter RB, et al. Single-level lumbar spine fusion: a comparison of anterior and posterior approaches. J Spinal Disord Tech 2002;15:355-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andersson GB, Mekhail NA, Block JE. Treatment of intractable discogenic low back pain. A systematic review of spinal fusion and intradiscal electrothermal therapy (IDET). Pain Physician 2006;9:237-48. [PubMed]

- Dowdell J, Erwin M, Choma T, et al. Intervertebral Disk Degeneration and Repair. Neurosurgery 2017;80:S46-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hallett A, Huntley JS, Gibson JN. Foraminal stenosis and single-level degenerative disc disease: a randomized controlled trial comparing decompression with decompression and instrumented fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1375-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuslich SD, Ulstrom CL, Michael CJ. The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica: a report of pain response to tissue stimulation during operations on the lumbar spine using local anesthesia. Orthop Clin North Am 1991;22:181-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gumbs AA, Hanan S, Yue JJ, et al. Revision open anterior approaches for spine procedures. Spine J 2007;7:280-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacob K, Patel M, Prabhu M, et al. 212. ALIF as a salvage procedure for TLIF pseudarthrosis: a clinical outcome study. Spine J 2022;22:S112-3. [Crossref]

- Crandall DG, Revella J. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion versus anterior lumbar interbody fusion as an adjunct to posterior instrumented correction of degenerative lumbar scoliosis: three year clinical and radiographic outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2126-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phan K, Rogers P, Rao PJ, et al. Influence of Obesity on Complications, Clinical Outcome, and Subsidence After Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (ALIF): Prospective Observational Study. World Neurosurg 2017;107:334-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choy W, Barrington N, Garcia RM, et al. Risk Factors for Medical and Surgical Complications Following Single-Level ALIF. Global Spine J 2017;7:141-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ullery BW, Thompson P, Mell MW. Anterior Retroperitoneal Spine Exposure following Prior Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair. Ann Vasc Surg 2016;35:207.e5-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim KJ, Kim DH, Lee JI, et al. Hounsfield Units on Lumbar Computed Tomography for Predicting Regional Bone Mineral Density. Open Med (Wars) 2019;14:545-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ebata S, Ohba T, Haro H. Integrated anatomy of the neuromuscular, visceral, vascular, and urinary tissues determined by MRI for a surgical approach to lateral lumbar interbody fusion in the presence or absence of spinal deformity. Spine Surg Relat Res 2018;2:140-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Teng I, Han J, Phan K, et al. A meta-analysis comparing ALIF, PLIF, TLIF and LLIF. J Clin Neurosci 2017;44:11-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rihn JA, Kirkpatrick K, Albert TJ. Graft options in posterolateral and posterior interbody lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:1629-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polikeit A, Ferguson SJ, Nolte LP, et al. The importance of the endplate for interbody cages in the lumbar spine. Eur Spine J 2003;12:556-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mummaneni PV, Dhall SS, Eck JC, et al. Guideline update for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. Part 11: interbody techniques for lumbar fusion. J Neurosurg Spine 2014;21:67-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rao PJ, Ghent F, Phan K, et al. Stand-alone anterior lumbar interbody fusion for treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Clin Neurosci 2015;22:1619-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee N, Kim KN, Yi S, et al. Comparison of Outcomes of Anterior, Posterior, and Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Surgery at a Single Lumbar Level with Degenerative Spinal Disease. World Neurosurg 2017;101:216-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hsieh PC, Koski TR, O'Shaughnessy BA, et al. Anterior lumbar interbody fusion in comparison with transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: implications for the restoration of foraminal height, local disc angle, lumbar lordosis, and sagittal balance. J Neurosurg Spine 2007;7:379-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Min JH, Jang JS, Lee SH. Comparison of anterior- and posterior-approach instrumented lumbar interbody fusion for spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Spine 2007;7:21-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McAfee PC, Boden SD, Brantigan JW, et al. Symposium: a critical discrepancy-a criteria of successful arthrodesis following interbody spinal fusions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:320-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim JS, Kim DH, Lee SH, et al. Comparison study of the instrumented circumferential fusion with instrumented anterior lumbar interbody fusion as a surgical procedure for adult low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. World Neurosurg 2010;73:565-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun D, Liang W, Hai Y, et al. OLIF versus ALIF: Which is the better surgical approach for degenerative lumbar disease? A systematic review. Eur Spine J 2023;32:689-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Härtl R, Joeris A, McGuire RA. Comparison of the safety outcomes between two surgical approaches for anterior lumbar fusion surgery: anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) and extreme lateral interbody fusion (ELIF). Eur Spine J 2016;25:1484-521. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson RD, Valore A, Villaminar A, et al. Pelvic parameters of sagittal balance in extreme lateral interbody fusion for degenerative lumbar disc disease. J Clin Neurosci 2013;20:576-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cahill KS, Martinez JL, Wang MY, et al. Motor nerve injuries following the minimally invasive lateral transpsoas approach. J Neurosurg Spine 2012;17:227-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cummock MD, Vanni S, Levi AD, et al. An analysis of postoperative thigh symptoms after minimally invasive transpsoas lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine 2011;15:11-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dakwar E, Cardona RF, Smith DA, et al. Early outcomes and safety of the minimally invasive, lateral retroperitoneal transpsoas approach for adult degenerative scoliosis. Neurosurg Focus 2010;28:E8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moller DJ, Slimack NP, Acosta FL Jr, et al. Minimally invasive lateral lumbar interbody fusion and transpsoas approach-related morbidity. Neurosurg Focus 2011;31:E4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rao PJ, Phan K, Giang G, et al. Subsidence following anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF): a prospective study. J Spine Surg 2017;3:168-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dennis S, Watkins R, Landaker S, et al. Comparison of disc space heights after anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14:876-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheung KM, Zhang YG, Lu DS, et al. Reduction of disc space distraction after anterior lumbar interbody fusion with autologous iliac crest graft. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:1385-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi JY, Sung KH. Subsidence after anterior lumbar interbody fusion using paired stand-alone rectangular cages. Eur Spine J 2006;15:16-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beutler WJ, Peppelman WC Jr. Anterior lumbar fusion with paired BAK standard and paired BAK Proximity cages: subsidence incidence, subsidence factors, and clinical outcome. Spine J 2003;3:289-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliorini F, de Maria N, Tafuri A, et al. Late diagnosis of ureteral injury from anterior lumbar spine interbody fusion surgery: Case report and literature review. Urologia 2023;90:579-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isiklar ZU, Lindsey RW, Coburn M. Ureteral injury after anterior lumbar interbody fusion. A case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:2379-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guingrich JA, McDermott JC. Ureteral injury during laparoscopy-assisted anterior lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:1586-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wymenga LF, Buijs GA, Ypma AF, et al. Ureteral injury associated with anterior lumbosacral arthrodesis in a patient who had crossed renal ectopia, malrotation, and fusion of the kidneys. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:772-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sasso RC, Best NM, Mummaneni PV, et al. Analysis of operative complications in a series of 471 anterior lumbar interbody fusion procedures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:670-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwender JD, Casnellie MT, Perra JH, et al. Perioperative complications in revision anterior lumbar spine surgery: incidence and risk factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:87-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Czerwein JK Jr, Thakur N, Migliori SJ, et al. Complications of anterior lumbar surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011;19:251-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feeley A, Feeley I, Clesham K, et al. Is there a variance in complication types associated with ALIF approaches? A systematic review. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2021;163:2991-3004. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amaral R, Ferreira R, Marchi L, et al. Stand-alone anterior lumbar interbody fusion - complications and perioperative results. Rev Bras Ortop 2017;52:569-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Escobar E, Transfeldt E, Garvey T, et al. Video-assisted versus open anterior lumbar spine fusion surgery: a comparison of four techniques and complications in 135 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:729-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santos ER, Pinto MR, Lonstein JE, et al. Revision lumbar arthrodesis for the treatment of lumbar cage pseudoarthrosis: complications. J Spinal Disord Tech 2008;21:418-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamdan AD, Malek JY, Schermerhorn ML, et al. Vascular injury during anterior exposure of the spine. J Vasc Surg 2008;48:650-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bateman DK, Millhouse PW, Shahi N, et al. Anterior lumbar spine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of associated complications. Spine J 2015;15:1118-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brau SA, Delamarter RB, Schiffman ML, et al. Vascular injury during anterior lumbar surgery. Spine J 2004;4:409-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni SS, Lowery GL, Ross RE, et al. Arterial complications following anterior lumbar interbody fusion: report of eight cases. Eur Spine J 2003;12:48-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baker JK, Reardon PR, Reardon MJ, et al. Vascular injury in anterior lumbar surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993;18:2227-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajaraman V, Vingan R, Roth P, et al. Visceral and vascular complications resulting from anterior lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg 1999;91:60-4. [PubMed]

- Rauzzino MJ, Shaffrey CI, Nockels RP, et al. Anterior lumbar fusion with titanium threaded and mesh interbody cages. Neurosurg Focus 1999;7:e7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rokito SE, Schwartz MC, Neuwirth MG. Deep vein thrombosis after major reconstructive spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:853-8; discussion 859. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith MD, Bressler EL, Lonstein JE, et al. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after major reconstructive operations on the spine. A prospective analysis of three hundred and seventeen patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:980-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inamasu J, Guiot BH. Vascular injury and complication in neurosurgical spine surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148:375-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuslich SD, Ulstrom CL, Griffith SL, et al. The Bagby and Kuslich method of lumbar interbody fusion. History, techniques, and 2-year follow-up results of a United States prospective, multicenter trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:1267-78; discussion 1279. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park SJ, Park JS, Lee CS, et al. Metal failure and nonunion at L5-S1 after long instrumented fusion distal to pelvis for adult spinal deformity: Anterior versus transforaminal interbody fusion. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2021;29:23094990211054223. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manzur M, Virk SS, Jivanelli B, et al. The rate of fusion for stand-alone anterior lumbar interbody fusion: a systematic review. Spine J 2019;19:1294-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sasso RC, Kenneth Burkus J, LeHuec JC. Retrograde ejaculation after anterior lumbar interbody fusion: transperitoneal versus retroperitoneal exposure. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:1023-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang BU, Choi WC, Lee SH, et al. An analysis of general surgery-related complications in a series of 412 minilaparotomic anterior lumbosacral procedures. J Neurosurg Spine 2009;10:60-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel MR, Jacob KC, Chavez FA, et al. Impact of Postoperative Length of Stay on Patient-Reported and Clinical Outcomes After Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Int J Spine Surg 2023;17:205-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dowlati E, Alexander H, Voyadzis JM. Vulnerability of the L5 nerve root during anterior lumbar interbody fusion at L5-S1: case series and review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus 2020;49:E7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farooq J, Pressman E, Elsawaf Y, et al. Prevention of Neurological Deficit With Intraoperative Neuromonitoring During Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Clin Spine Surg 2022;35:E351-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Konbaz F, Aldakhil S, Alhelal F, et al. Iatrogenic contralateral foraminal stenosis following lumbar spine fusion surgery: illustrative cases. J Neurosurg Case Lessons 2023;5:CASE2317. [Crossref] [PubMed]